The Four Growth Frameworks You Need to Build a $100M Product

by Brian Balfour

Welcome to my guide on building and growing a $100M revenue product! I've been lucky to have been part of building, advising, or investing in 40+ tech companies in the past 10 years. Some $100M+ wins. Some, complete losses. Most end up in the middle.

One of my main observations is that there are certain companies where growth seems to come easily, like guiding a boulder down hill. These companies grow despite having organizational chaos, not executing the “best” growth practices, and missing low hanging fruit. I refer to these companies as Smooth Sailers - a little effort for lots of speed.

In other companies, growth feels much harder. It feels like pushing a boulder up hill. Despite executing the best growth practices, picking the low hanging fruit, and having a great team, they struggle to grow. I refer to these companies as Tugboats - a lot of effort for little speed.

What's the difference between these two types of companies? This is a question I’ve pondered for a long time and have pieced together a framework to explain the difference. The framework has many implications for how you seek out growth and build a company.

Part 1: Why Product Market Fit Isn't Enough

Before I explain the high level framework, we need to start with what the difference between these two types of companies isn’t...

It’s Not Just Great Product

The “go-to” answer for almost every question in startups, is “build a great product.” Every time I hear that answer it feels completely unsatisfied. Building a great product is a piece of the puzzle, but it’s far from the full picture.

There are great products that never reach $100M+.

There are also terrible products by many people's definition that reach far greater than $100M+. If you’ve ever used Workday, you know what I’m talking about. (At the time of this writing, Workday is worth $20 billion.)

"Build a great product" can't be the answer to most growth questions, if the above two statements are true. It is certainly a starting point, but not the answer.

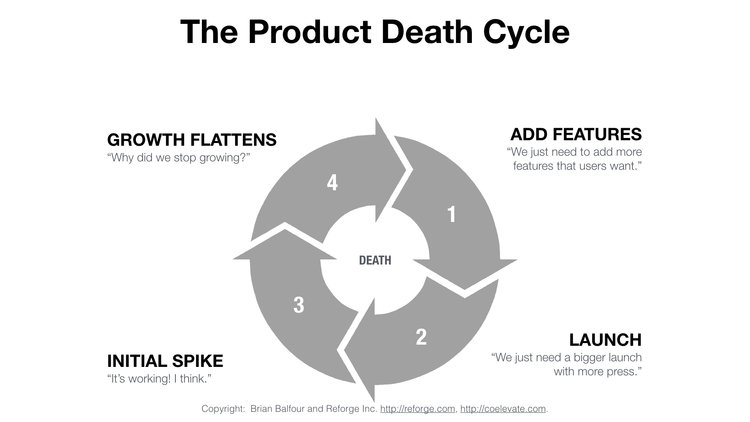

The problem with the answer of “build a great product” is that it leads to something that Andrew Chen and I talk about extensively in the Reforge Growth Series called the Product Death Cycle. The Product Death Cycle was originally coined by David Bland of Precoil.

These are the phases of the product death cycle:

Add New Features: Team adds new exciting product features.

Launch: Features are launched with some press.

Spike: A short term spike in growth occurs.

Growth Flattens: Within weeks the growth flattens off.

(repeat) Add New Features: Team ends up back where they started, adding new features to get another spike.

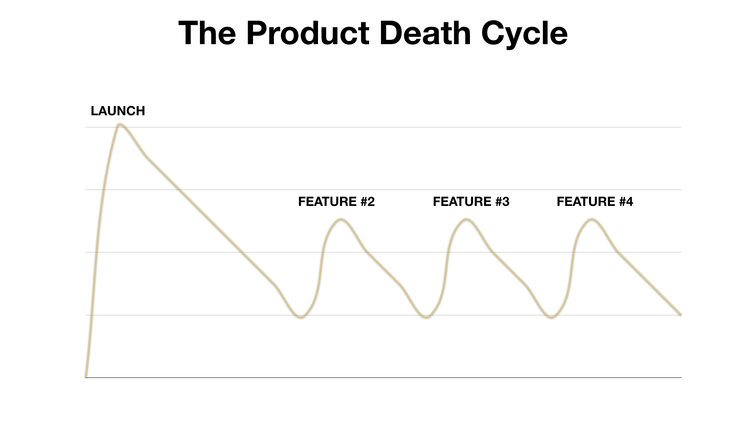

In terms of a growth curve, it looks similar to this:

This isn’t the type of curve we are looking for. Subscribing to the mantra that all you have to do is “build a great product” is submitting yourself to an “if you build, they will come mentality.” Happy dreaming.

It’s Not Just Product Market Fit

The second “go-to” answer is product market fit. While product market fit is a component of the framework, it is far from the answer. The issue with the product market fit mantra is that we have taken it to the extreme and developed tunnel vision. Statements like “Product Market fit is the only thing that matters” have become more common. It is not the only thing that matters.

There are plenty of companies that have all the product market fit signals (I’ll talk about these signals in the next post) but still struggle to grow, and definitely don’t reach a $100M+ product.

I’m lucky to be an investor in WonderSchool. Prior to pivoting to WonderSchool, the team developed Soldsie, a tool to help brands sell better on Instagram and Facebook. Soldsie has product market fit by all measures (solid NPS, good retention, organic growth), but despite great efforts, growth for Soldsie was slow, and the company was not growing at a venture-backed pace.

There are tons of similar examples in startup land. The main point is: product market fit is not the only thing that matters.

It’s Definitely Not Growth Hacking

One of the other common answers that has emerged is “Growth Hacking.” You have a great product, you have product market fit, now all you need is to find a growth hack to grease the growth wheels. No other term makes my stomach churn more.

While the term started with good intentions, it has morphed into a concept around hacktics - that there is a tip, trick, secret, or tool that is going to unlock growth in your business. The problem with hacktics are that they are short lived and never sustainable.

Before tactics you need a growth process. But before a growth process you need a strategy. This framework is all about how you construct your strategy and position yourself for "Smooth Sailer" growth.

What is the difference between Smooth Sailer and Tugboat companies?

It’s not great product, product/market fit, or growth hacking. Then what is it?

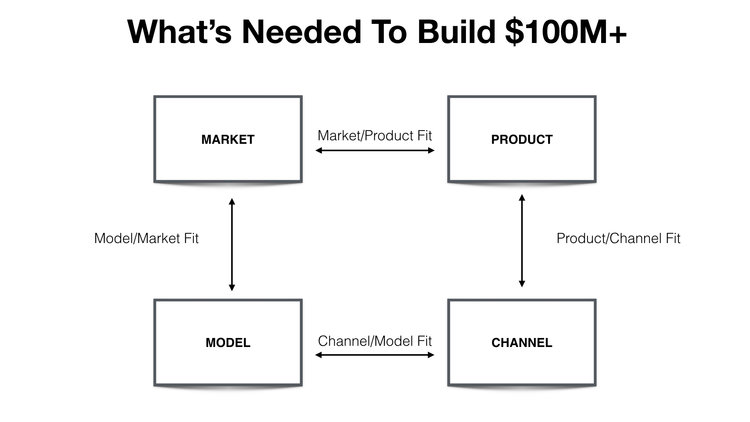

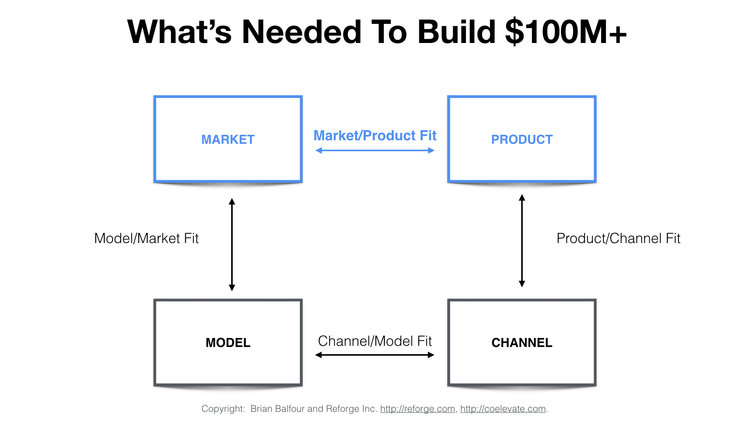

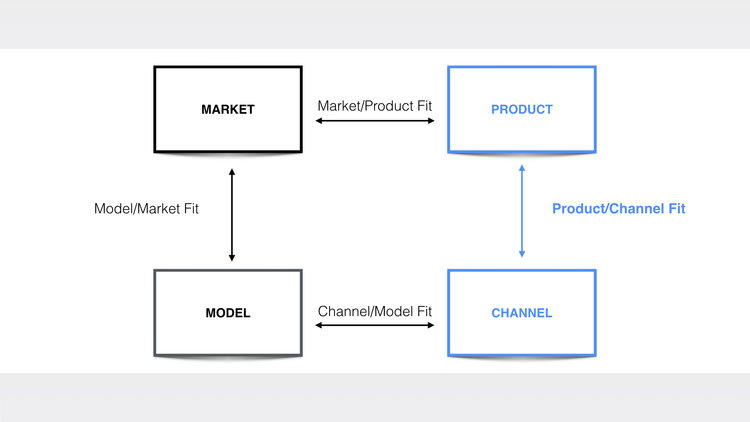

The difference between the $100M+ companies, and those that struggle are the ones that are able to make four pieces in a puzzle fit:

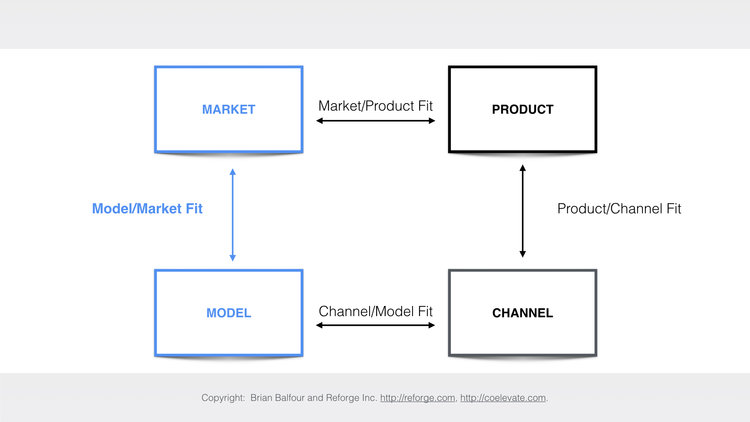

There are four essential fits: Market Product Fit, Product Channel Fit, Channel Model Fit, Model Market Fit. I'm going to dedicate a post to each of these fits, along with how you can apply this framework.

There are three extremely important points I want to hammer home through out these posts:

You need to find four fits to grow to $100M+ company in a venture-backed time frame.

Each of these fits influence each other, so you can’t think about them in isolation.

The fits are always evolving/changing/breaking. When that happens, you can’t simply change one element, you have to revisit and potentially change them all.

Part 2: The Road to a $100M Business Doesn’t Start with Product

In the previous section of this guide, I made the point that Product Market Fit isn't the only thing that matters. It is actually only one of four fits needed to grow a product to $100M+ in a venture-backed time frame.

While Product Market Fit isn't the only thing that matters, it is important, so it makes sense that there are no shortage of blog posts explaining Product Market Fit, and how to get it.

Instead of echoing the many great Product Market Fit explainer posts out there, I'm going to focus on the 5 elements of Product Market Fit that I believe are most misunderstood and overlooked:

The wrong way to search for Product Market Fit.

Why we should be thinking about it as Market Product Fit.

How we defined our market and product hypotheses for early versions of HubSpot Sales.

What the search for market product fit looks like in reality, not just in theory.

Qualitative, Quantitative, and Intuitive signals of market product fit.

In 2008 I co-founded a company called Viximo. We raised $5M out of the gate from top tier VCs to build a virtual goods platform (this was pre-Facebook platform days). I remember sitting in one of our first board meetings saying something similar to:

This probably seems like a reasonable statement to many (I hear it all the time in startup pitches), but there’s one serious problem with it. We had a solution (virtual goods platform) that was looking for a problem and a market (dating sites, social networks, etc.). In other words, we were putting the cart before the horse.

What we should have done instead was to focus on the problem and market, then search for the solution. This common mistake is why I prefer “Market Product Fit” over the terminology “Product Market Fit.”

The reason for this is because the real problem is something experienced within your market and by your audience, not something that lives within your product. While that phrasing might sound like a small change, language matters. How we word things affects how we think about things.

Searching For Market Product Fit The Right Way

When I got to HubSpot, I joined a brand new division in the company with just six other people. We were tasked with building the road to a second $100M line of business (the HubSpot Marketing product being the first), so it was a lot like running a startup within the larger Hubspot org.

Luckily, by this point I had learned my lesson from the Viximo days. Rather than focusing on the product first, we narrowed in on defining the market.

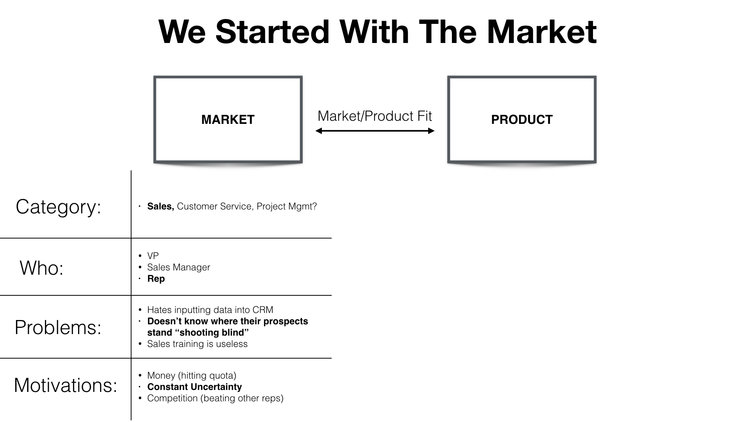

There were four key market elements that we looked at:

Category. What category of products does the customer put you in?

Who. Who is the target audience within the category? There are always multiple personas within a single category, so this breaks it down further.

Problems. What problems does your target audience have related to the category?

Motivations. What are the motivations behind those problems? Why are those problems important to your target audience?

While I find most companies really understand the “category” and the “who,” defining the problems and the motivations behind those problems is far more important.

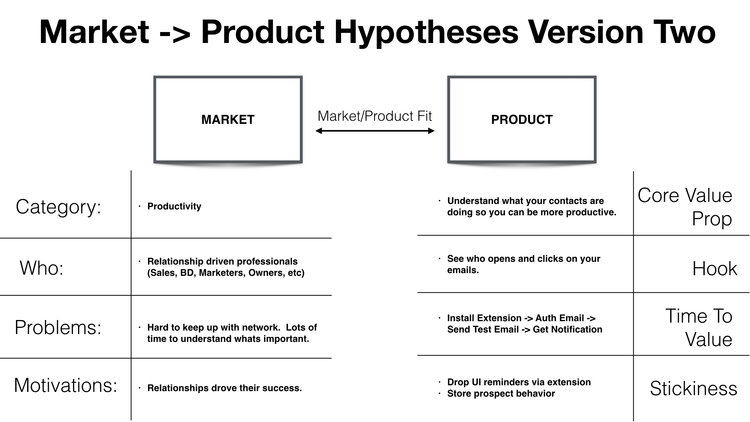

Here is what these four elements roughly looked liked for our HubSpot division:

We explored multiple things in each bucket, but where we ultimately ended up the following combination of market elements:

Category. Sales Software

Who. The individual contributor. There were also two sub-types of ICs: SDRs and Account Reps.

Problem. Not knowing where a prospect or client stood in the process.

Motivation. A couple of motivations: 1) Money. Knowing where a prospect was led to better prioritization and selling which led to more closing. 2) Uncertainty. The target audience life was filled with constant uncertainty. Relieving that uncertainty was a big deal.

Out of this problem and market definition, the team started thinking about the product (solution). Through the awesome work of Christopher O’Donnell, Dan Wolchonok and a few others, they formed a really simple tool called Signals, which was then rebranded to Sidekick, and then rebranded again to HubSpot Sales (more on this later).

The product was extremely simple. It consisted of a Chrome extension that, with a click of a checkbox, let you track your emails and get instant notifications on who opened and clicked on your emails.

While this seems simple, back then our initial audience thought it was some voodoo magic. It helped solve that problem of knowing where their prospects stood. They now had an indication of where the prospect was -- if the prospect saw the email, if they clicked or viewed a proposal, if they forwarded it around their company, and more. The core product was free, with a $10 tier for unlimited notifications.

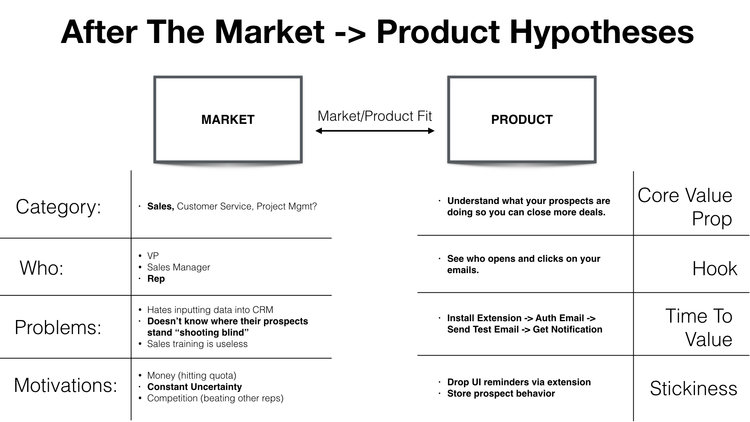

This brings us to the next group of elements in defining Market Product Fit -- the product hypotheses elements. The four main elements that were important to define as product hypotheses were:

Core Value Prop. What was the core value prop of the product? How did it tie to the core problem?

Hook. How could the core value prop be expressed in the simplest terms?

Time To Value. How quickly could we get the target audience to experience value.

Stickiness. How and why will customers stick around? What are the natural retention mechanisms of the product?

For the Signals product, the hypotheses looked like this:

Core Value Prop. Understand what your prospects are doing and thinking, so you know how to sell better.

Hook. See who opens and clicks on your emails.

Time To Value. Quick (less than 1 minute). Install Extension -> Auth Email -> Send Test Email -> Get Notification. That instant notification demonstrates the value.

Stickiness. High. Product only requires a user to keep checkbox checked to keep receiving notifications, and every notification reengages people with the product. With the Chrome Extension, we could also drop hints in the UI to further keep people engaged.

These hypotheses are extremely important to lay out. As you will see in future posts of the series, it informs and deeply affects the other components of the framework like Channel and Model.

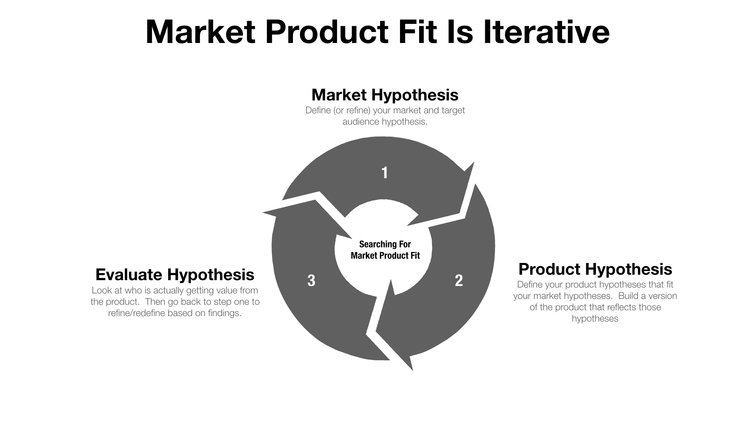

The Reality Of Searching For Market Product Fit

In practice, the search for market product fit is never a straight line. Instead, it happens over multiple cycles of iteration. You start with a market, build an initial version of the product, look at who actually gets value from the product, then redefine the market and redefine the product.

This is exactly what happened with Signals. We laid out the early hypotheses above. But once we dug in, we found a lot more target personas outside of our sales audience hypothesis were getting deep value out of the product. Great news! We found a lot of marketers, business owners, and other professionals using the product just as deeply as the sales professionals that were our core personas.

So, we refined the category, the who, the problem, and the motivations to what we were actually seeing. The second version looked liked this:

The refinement didn’t stop here. We had another major shift about a year in which I’ll talk about in future posts.

Market Product Fit Is Not Binary

The iteration cycle of market product fit brings us to another key point:

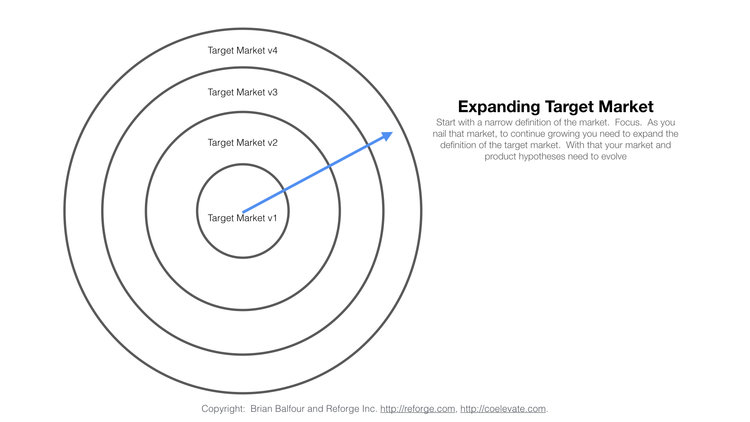

Market Product Fit is not binary. It’s also not a single point in time.

A better way to think about Market Product Fit is on a spectrum of weak to strong.

When you imagine Market Product Fit as a binary concept, it implies that your market and product components don’t change. We know in practice, as in the Signals case, that this is far from the truth. Once again we should be letting the market lead the way in this ongoing process.

There are two primary ways that the market changes for a startup.

1. EXPANDING MARKET DEFINITION

Most startups start with a very niche market and expand the definition of their market outwards into larger and larger markets. Think of it like starting at the center of a bullseye and expanding out into concentric circular layers.

To expand into these concentric layers, the product typically needs to change to maintain the strength of market product fit.

Sometimes moving into these segments of a target audience are an iteration. Other times, they require much bigger changes. Understanding how big of a change is required starts with a deep understanding of the audience’s problems and motivations.

2. THE MARKET EVOLVES

At the same time, markets don’t sit still. That means the markets with which you have strong Market Product Fit will evolve over time.

For example, think about the shift from web to mobile. Facebook was one of the companies who successfully made the tough transition. Sheryl Sandberg has said that to do this, the company didn’t ship new features for a whole year just to make sure they nailed this market transition.

Signals Of Market Product Fit

If Market Product Fit isn’t binary, then how do you know if you have Market Product Fit? There has been a decent amount written about this, but most of it doesn’t reflect reality.

With almost everything, you need to combine qualitative measurements with quantitative measurements with your own intuition. We trick ourselves when we only look at one of these areas. It’s a lot like trying to get a full picture of an object with only a one dimensional view.

How do we combine qualitative, quantitative and intuition indicators to understand how strong of Market Product Fit we have?

1. QUALITATIVE

The typical starting point with measuring Market Product Fit are qualitative indicators because they are the easiest to deploy and require the least amount of customers and data.

To get a qualitative understanding, my preference is to use Net Promoter Score (NPS). If you are truly solving the audience’s problem, then they should be willing to recommend your product to a friend.

The biggest downside with qualitative information (vs quantitative) is that it carries a higher probability for generating a false positive result, so take it with a grain of salt.

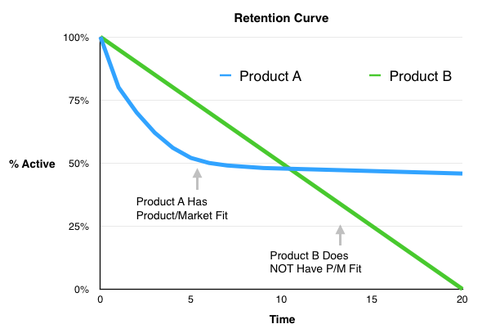

2. QUANTITATIVE

There are two quantitative measures to understand Market Product Fit: Retention Curves and Direct Traffic.

In 2013 I first spoke about how flat Retention Curves indicate Market Product Fit.

There are some businesses where you can still have Market Product Fit with retention curves that aren’t flat. For example, an online dating product has natural churn built into success. A new insurance tech company where success for a customer is finding an insurance plan will also have natural churn built in. But for 80% of B2C and B2B products out there, flat retention curves is what you are looking for.

The second quantitative indicator is direct traffic. Direct traffic is typically the result of word of mouth. If you are truly solving an audience's problem, they tend to tell friends. It might not be a lot of direct traffic, but there should be some.

The two combined (flat retention curves and direct traffic) mean that a product with Market Product fit will grow naturally without additional efforts like paid marketing.

Sometimes I like to ask the question, “If you turned off all your marketing efforts today, would you keep growing?” The answer should be yes. The growth might be slow, but it should still be naturally growing.

3. INTUITION

Intuition is about gut feeling, and it’s hard to verbalize. It’s hard to understand intuitively if you have Market Product Fit unless you’ve been part of some situations where you don’t have it and some situations where you do have it. I’ve been in both situations. So has Peter Reinhardt, founder/CEO of Segment, who I think has had the best description of how Market Product Fit feels:

“Product market fit doesn't feel like vague idle interest. It doesn't feel like a glimmer of hope from some earlier conversation. It doesn't feel like a trickle of people signing up. It really feels like everything in your business has gone totally haywire. There's a big rush of adrenaline from customers starting to adopt it and ripping it out of your hands. It feels like the market is dragging you forward.

I think the Dropbox founders said this best that product market fit feels like stepping on a landmine...when we did find product market fit, I thought for sure, this is too tiny to matter but it actually solved a real problem and the market demanded it and ripped it out of our hands.”

The point here is when you have strong Market Product Fit, it feels like the market is pulling you forward vs you pushing something on the market.

The Key Points

Start with the market (problem), then the product (solution). Not the other way around.

Define your market hypothesis using Category, Who, Problems, Motivations with most of your work going into Problems/Motivations.

Define your product hypothesis using Core Value Prop, Hook, Time To Value, Stickiness.

Think of Market Product fit as a cycle.

Understand that Market Product fit is not binary. Instead, it’s a spectrum of weak to strong.

To understand if you have Market Product Fit, combine the qualitative, quantitative and intuitive indicators.

Part 3: Product Channel Fit Will Make or Break Your Growth Strategy

Earlier, I discussed our common obsession with Product Market Fit that has led to false beliefs such as “Product Market Fit is the only thing that matters.” A byproduct of that false belief are statements such as:

“We are focused on product-market fit right now. Once we have that we’ll test a bunch of different channels.”

There are two major issues with this statement. I’ll break them down separately.

1. Products Are Built To Fit Channels, Not The Other Way Around

The first issue with that statement is that it is saying that channels will mold to the product you are building and as a result you think about product and channel separately in silos. But if you think about your product and channels in silos, then you will end up trying to fit a square peg through a round hole. Why? Because…

Products are built to fit with channels. Channels do not mold to products.

Let that statement sink in for a second because it is an important one.

Products are built to fit with channels, not the other way around. The reason for this is that you do not define the rules of the channel. The channel defines the rule of the channel.

Facebook defines the rules of what content and feed items appear in people’s feeds. They also define what is allowed via their API’s. They also define which ads get shown and how expensive they are.

Google defines what content appears in the top ten search results. They also control what the top ten search results look like. They determine what ads appear and the rules that govern their cost.

Email clients such as Gmail determine what is spam, what ends up in the promo box, and what the content format is allowed in emails.

We could run through this for every major distribution channel out there.

You control your product, you do not control the channel. So you need to change the things within your control to fit with the things that you do not control.

What are some general elements of products that fit with different categories of channels:

Virality. For virality to be a high ceiling channel, a product at a minimum needs

Quick Time To Value. Virality thrives when the viral cycles are short.

Broad Value Prop. Value prop of the product needs to be applicable to large percentage of a user's network (branching factor).

Network Makes Product Better. Ideally the product value increases the more of your network is on it.

Paid Marketing. To have product channel fit with paid marketing:

Quick Time To Value - Users have less patience to find value when coming from an ad.

Medium to Broad Value Prop - Value prop needs to be fairly broad due to targeting constraints of ad channels.

Transactional Model - Product is built to extract transactional value to fund paid marketing.

UGC SEO. To have product channel fit with UGC SEO:

UGC - Product needs to enable users creating millions of pieces of unique content.

Motivation to Contribute - Product needs to have the core motivation to contribute content.

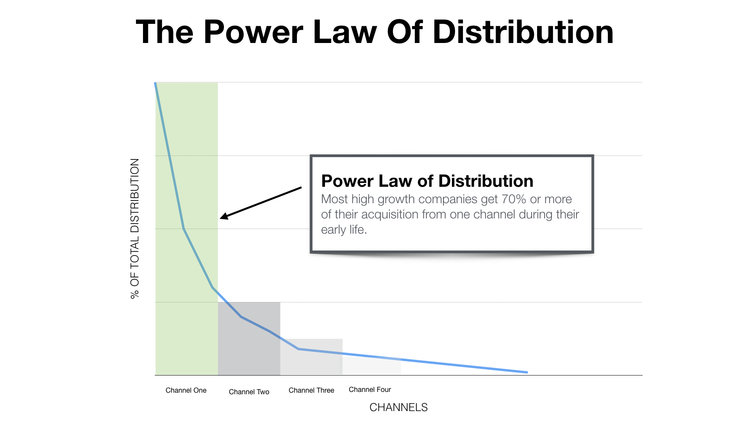

2. The Power Law of Distribution

The second problem with that original statement is “we’ll test a bunch of different channels.”

In his book, Zero To One, Peter Thiel pointed out why this is wrong:

“The kitchen sink approach doesn’t work. Most companies get zero distribution channels to work. If you get just one channel to work you have a great business. If you try for several but don’t nail one, you’re finished. Distribution follows the power law."

That last part is key - “distribution follows the power law.” In other words, at a given moment in time a company that has product channel fit will get 70%+ of their growth from one channel.

If you look at most $100M+ companies, you will find this to be true:

UGC SEO: TripAdvisor, Yelp, Glassdoor, Pinterest, Houzz all got 70% of their growth from UGC SEO.

Virality: WhatsApp, Evernote, Dropbox, Slack all got 70%+ of their growth from some form of virality.

Paid Marketing: Supercell, Squarespace, Blue Apron all got 70%+ of their growth from some form of paid marketing.

The power law of distribution exists because of the concept of product channel fit. Companies that are able to achieve product channel fit with multiple channels are rare, but end up being monsters. LinkedIn is the perfect example where over time they've achieve Product Channel Fit with Virality, UGC SEO, and different forms of Inbound and Outbound Sales.

Product Channel Fit

Product Channel Fit when your product attributes are molded to fit with a specific distribution channel. As a result you can't think about Product and Channel as silos.

Product Channel Fit has a few immediate implications:

1. You shouldn’t take a shotgun approach to testing channels.

It is better to prioritize and tackle one or two at a time in pursuit of your power law channel. Here is a step by step on how to test and prioritize your growth channels.

2. Over time you shouldn’t seek to diversify channels for the purpose of diversification.

You should seek out other channels in case product channel fit breaks and need to transition to a new one (more on this below).

3. Don't have team members focused on user acquisition and team members focused on product in silos from each other.

This is partly why cross functional growth teams have emerged.

Product Channel Fit Is Your Blessing and Your Demise

You know the saying that your strength is also your biggest weakness? Well that applies to Product Channel Fit. Product Channel Fit is what can make your company, and also what can kill it.

The reason is because Product Channel Fit (just like all the other fits) is always evolving and can break as a new channel emerges or an old channel gets killed off. Let’s look at examples of both.

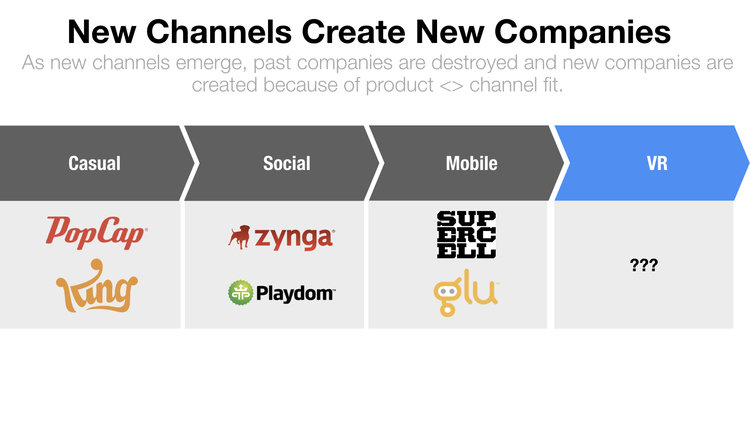

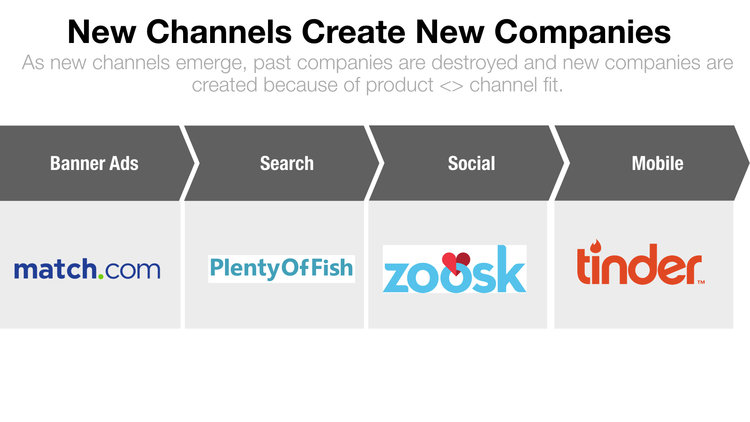

1. New Channels Emerge

Every so often a new major channel emerges in the ecosystem. When this happens you typically see two things:

Companies in the old channel will try and copy/paste their product into the new channel.

Because of Product Channel Fit, #1 doesn’t work and leaves the door open for new companies to emerge.

There has been no clearer example of this than the gaming industry.

In the early 2000’s desktop web portals were the major channel. You had big flash gaming companies emerge like PopCap. Then in early 2007, social emerged as a new channel with the Facebook platform. The flash web gaming companies tried to just copy/paste their games into the new channel and it didn’t work. They left the door open for companies like Zynga and Playdom to emerge and build products that fit with the new channel.

Then a few years later mobile emerged as a new channel. Zynga tried to copy/paste their popular games into mobile which didn’t work. The door was open for companies like Supercell to emerge who built new products to fit with the new channel.

Zynga, PopCap, King, etc are still around today. But they took a really long time to transition to the new channels correctly and as a result some opportunity was captured by others.

This hasn’t just happened with gaming. Online Dating is another category where there are tons of examples:

Match and others emerged during the first web boom and got most of their traction via banner ads. Then SEO emerged as a major channel and PlentyOfFish emerged as a contender. Then the social platforms came along and Zoosk and others emerged. Then mobile came along and Tinder emerged.

All along the way the same thing happened. New channel emerges, old player tries to copy/paste, opens door for new company/product to emerge with Product Channel Fit with the new channel.

This is worth repeating here. Products need to be molded to the channel. The channel does not mold to the product. Product Channel Fit creates new companies. But if not managed properly, can also kill your company.

1. Old Channels Get Killed Off

In late 2011 Pinterest hit an inflection point and their growth started to take off. One of the reasons were they hit product channel fit. The channel was viral sharing to Facebook's feed through their API. But around end of 2012 Facebook started killing off the API's that enabled this channel. Many reported on Pinterest's slowing growth.

This is an example of when you have Product Channel Fit, but it breaks due to a channel getting killed off. Many companies were also effected by Facebook killing off this channel. Pinterest was one of the few that transitioned successfully. They ended up transitioning to a UGC SEO channel which has driven their growth ever since.

Part of that transition over the long term was that Pinterest also changed their product focus from a social product to more of a personal utility. Once again, you have to mold the product to the channel. You can't think about them in silos.

In the next sections, we'll talk about Model Channel Fit and Model Market Fit.

Part 4: Get Out of the ARPU-CAC Danger Zone with Channel Model Fit

Channel Model Fit is simple - channels are determined by your model.

First, what do I mean by “Model?” The two most important elements of your model are:

How Your Charge - For example, free (monetized with ads), freemium, transactional, free trial, one year up front, etc.

Average Annual Revenue Per User - What the average $$ you make from a customer/user per year.

A common question I get at this point is: “Why only look at average annual revenue versus full LTV?”

The reason is because most startups need to keep their payback period to less than one year. If it is much longer than one year then you will need a lot more cash to fund growth. This is a catch-22 because companies that are growing fast are able to raise a lot of cash, but if you need a lot of cash to grow fast (i.e. high payback periods) you will never show the momentum to raise the money needed.

Let's return to the definition of Channel Model Fit, that channels are determined by your model, and look at why that is.

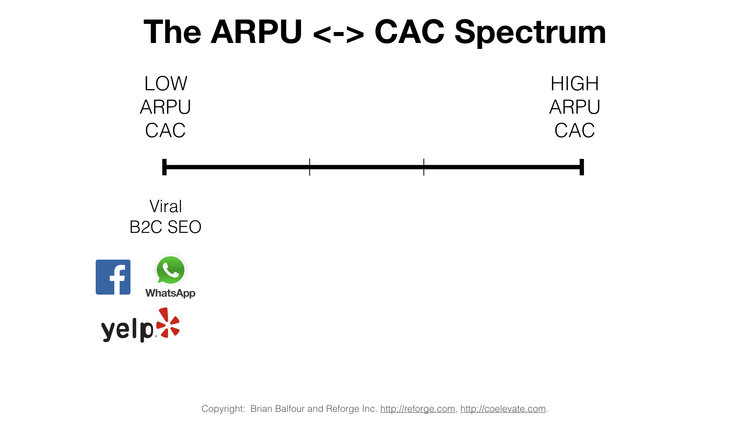

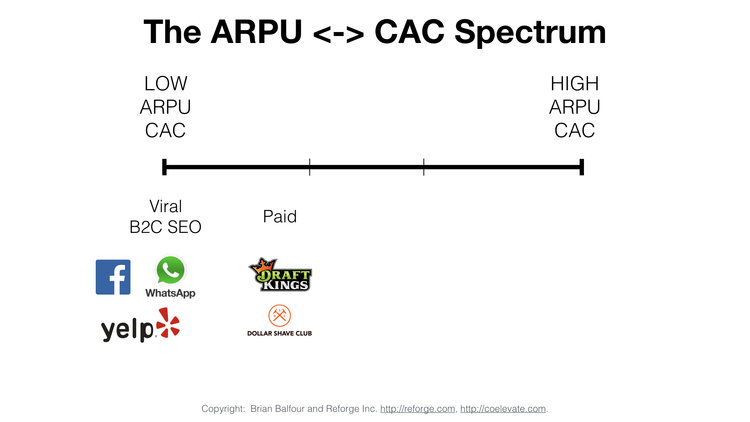

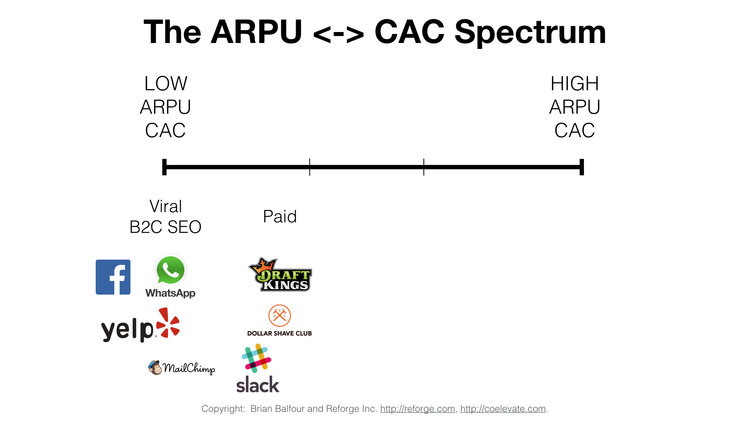

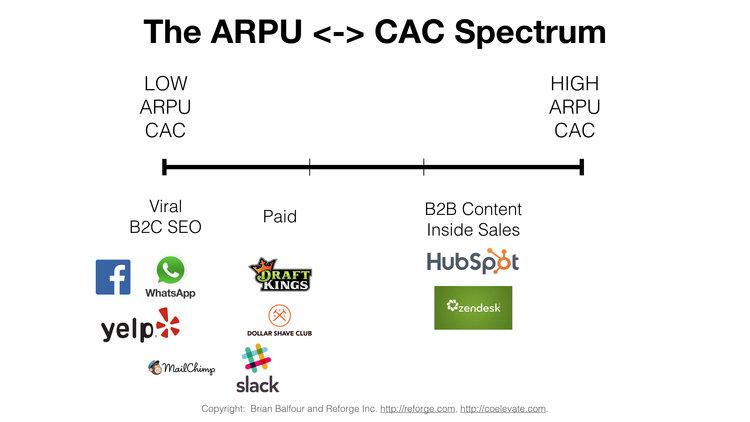

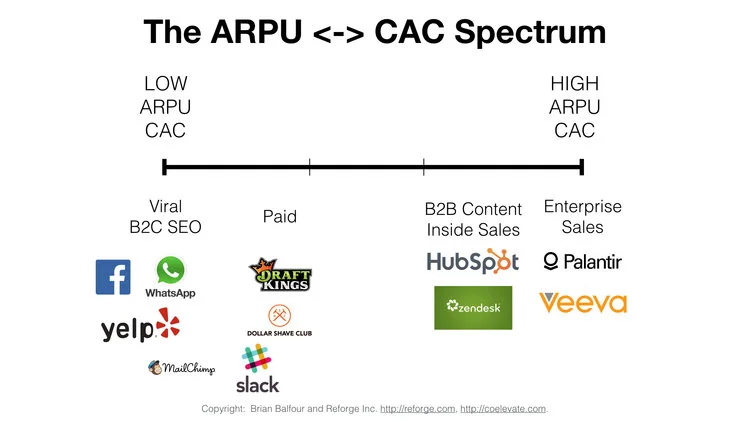

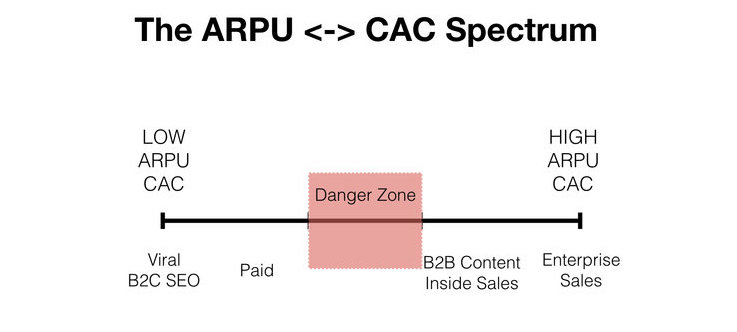

The ARPU <-> CAC Spectrum

Every business lives on the ARPU ↔ CAC Spectrum. On far left you have businesses that have low ARPU and as a result have to use low CAC channels to drive customers. On the far right you have businesses that have high ARPU and as a result are able to use high CAC channels. I'll walk through some examples:

Most B2C companies driven by an ads model — companies like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Yelp — live on the left hand end of the spectrum. They have low ARPU, and therefore have Product Channel Fit with low CAC channels like Virality and UGC SEO.

One step over on the spectrum you have slightly higher ARPU businesses. Think of something like Dollar Shave Club or DraftKings. Businesses with transactional models (i.e. subscription e-commerce) typically live here. Because they have higher ARPUs they can take advantage of higher CAC channel like Paid Marketing.

In the B2B world you also have B2B products like MailChimp, Slack, or SurveyMonkey that live on this end of the spectrum as they take advantage of viral and paid channels to drive most of their volume.

Shifting over to the right hand end of the spectrum you have higher ARPU businesses (typically B2B Mid Market companies) like HubSpot and Zendesk. They have higher ARPUs and can therefore take advantage of high CAC channels such as content marketing, inbound/inside sales, or channel partnerships.

Finally on the far right hand end of the spectrum you have very high ARPU businesses (6 to 7 figures) and therefore take advantage of very high CAC channels such as enterprise and outbound sales. Companies like Palantir and Veeva exist on the very far end.

The ARPU-CAC Danger Zone

If you notice above, I left the middle of the spectrum blank. This is the ARPU-CAC Danger Zone.

I call it the danger zone because companies that end up in this zone have a much higher failure rate because they lack Channel Model Fit. These companies' problem with Channel Model Fit can be broken down into two major reasons.

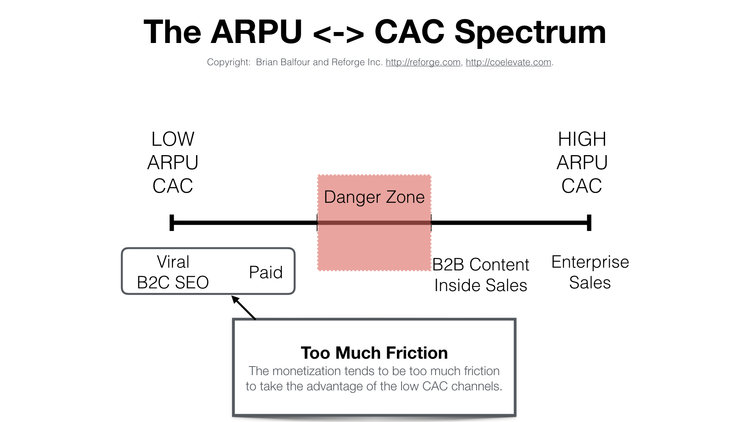

1: Too Much Friction For Low CAC Channels

Low CAC channels require low friction products (quick time to value) and low friction models. Companies in the danger zone have ARPUs that are too high and introduce too much friction to use low CAC channels.

For example, if you clicked on an ad for an interesting product and found it to be $500, what are the chances you would buy? Pretty minimal. The higher the price, the greater the friction. The greater the friction, the less effective the lower CAC channels are because they just don't influence a user's decision enough.

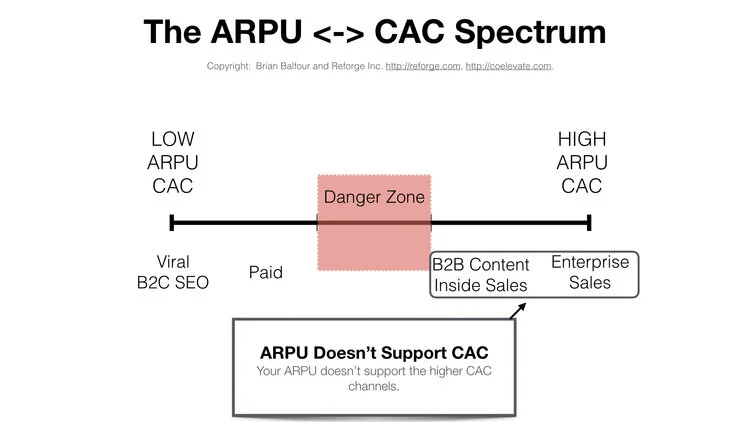

2: ARPU Doesn't Support Higher CAC Channels

Companies in the danger zone also have ARPUs that are too low to support the higher CAC channels. These companies end up with terrible unit economics as they're forced to shell out more than they can bring in with that spend.

Can Companies Exist In The Danger Zone?

The danger zone does not imply that a business can't exist there. You can have a business here, but your acquisition strategy ends up a patchwork of bits and pieces from a lot of different channels rather than owning one channel. Piecing together a lot of little channels is much more difficult to execute well, and ends up in slower overall growth. Over time, this can lead to the company's failure.

Tom Tunguz of Redpoint Ventures did a great analysis to show that there are companies that have succeeded in the “no man's land” of the ARPU-CAC Danger Zone. But Tunguz makes the key point that the analysis itself suffers from Survivorship Bias. If we were able to analyze all startups every created and classify them if they were in the danger zone, we would find a much higher failure rate.

The ARPU ↔ CAC Spectrum for Product Tiers

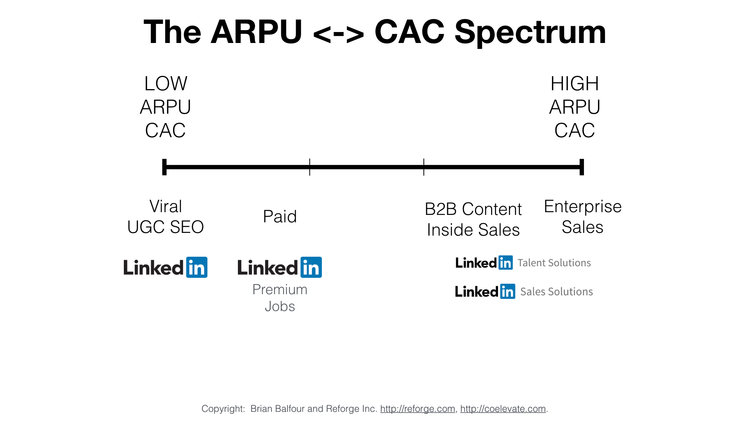

Channel Model Fit doesn't just exist for overall products and companies; it exists at a product tier level as well. LinkedIn is a great example of this.

LinkedIn Free - On the left end of the spectrum they have their free product driven by Virality and UGC SEO. Low ARPU (advertising) therefore low CAC channels.

LinkedIn Premium/Jobs - One step over they have LinkedIn Premium and LinkedIn Job Postings. Higher ARPU, therefore they can take advantage of higher CAC channels like Paid. They are in the advantageous position where they also own the channel.

LinkedIn Talent, Sales, and Learning Solutions SMB - LinkedIn also has B2B products in Talent Solutions, Sales Solutions, and Learning Solutions for small and medium sized businesses. Here they use mostly Content Marketing and Inside Sales.

LinkedIn Talent, Sales, and Learning Enterprise - They also have enterprise tiers of their B2B products and use outbound enterprise sales to drive those.

The fact that LinkedIn has been able to layer on multiple products with Product Channel Fit and Channel Model Fit is partially why they are worth $26B at the time of this writing.

Get these four fits to align for one product, and you have a $1B company. Get them to fit multiple times within your business and you likely have a $10B+ company.

Implications Of Channel Model Fit

There are two primary implications of Channel Model Fit:

1. Don't Treat Model and Channel In Silos - You can't think about your model and your channel in silos because the two go hand in hand. If you are making changes to your model (pricing, how you charge, etc.), you also need to consider your channel to make sure you still have Channel Model Fit. I see a lot of entrepreneurs make changes to pricing and expect the other components to continue working, but this kind of model-level change can make or break the viability of the key channels you've been counting on.

2. Don't Treat Channel Model Fit In A Silo - If your channel is determined by your model, but your product is built to fit the channel...see where I'm going with this? This is why you can't treat these fits separately and need to have working hypotheses for each.

In the next section, we'll go through the fourth framework Model Market Fit. After that we will bring all four frameworks together and put them into action.

Part 5: The Model Market Fit Threshold and What it Means for Your Growth Strategy

Model Market Fit

Model Market Fit is the concept that your market (and # of customers within your market) influence your model.

The first time I heard about the underlying concept of Model Market Fit was from Christoph Janz @ Point Nine Capital. He wrote a post called The Five Ways To Build A $100M Business. He then followed that up with Three More Ways, but I'm going to focus on the first five as they represent most of the $100M+ outcomes out there.

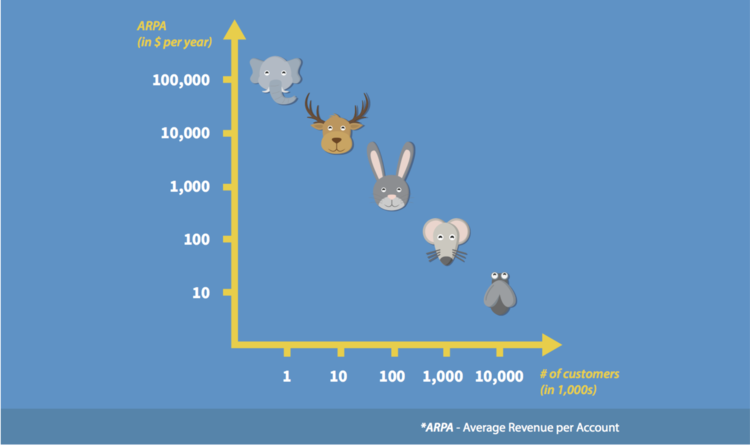

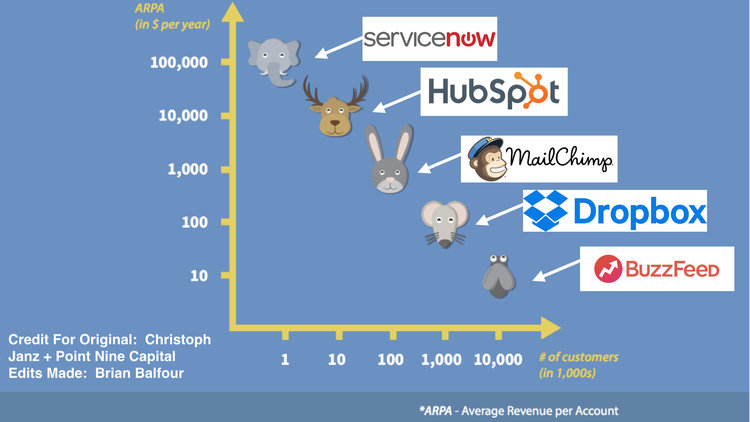

In Christoph's post he published the following graph:

Credit: Christoph Janz and Point Nine Capital

On the Y-Axis is the average annual revenue per customer that you generate from your model. On the X-Axis is the total number of customers you need to create a $100M+ Business. Most companies end up falling in one of five areas that Christoph named:

Elephants - Products that get 1,000 customers paying $100K+ year. These are typically products built for enterprise customers like ServiceNow.

Moose - Products that get 10,000 customers paying you $10K+ per year. These are typically products built for the mid market like HubSpot.

Rabbits - Products that get 100,000 customers paying $1K per year. These are typically products targeting small businesses like SurveyMonkey, Mailchimp, or Gusto. Products targeting consumers at high value moments also live here. For example companies in real estate, insurance, etc.

Mice - Products that get 1M customers paying $100 per year. These are typically products that target prosumers like Dropbox, or companies that are subscription ecommerce like Ipsy or Dollar Shave Club.

Flies - Products that get 10M customers generating $10 per year typically via ads. Facebook, Snapchat, Buzzfeed, etc. all live here.

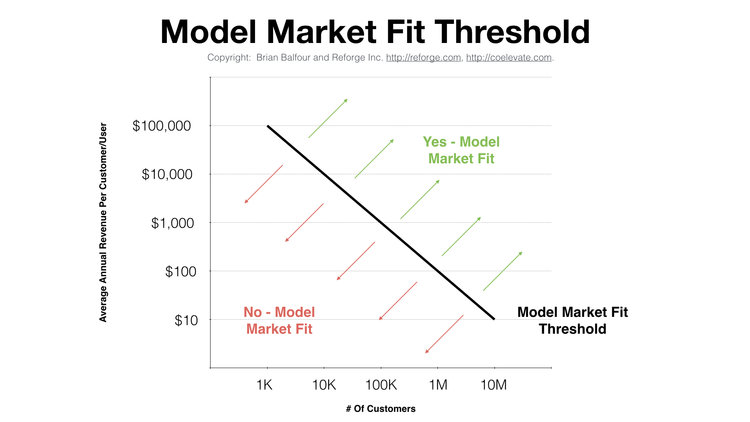

What we can do is draw a line down the graph. This is what I call the Model Market Fit Threshold.

If your business ends up above this threshold, then you have Model Market Fit. If you are below the threshold, then you don't have Model Market Fit.

Understanding If You Have Model Market Fit

Of course, once you have a $100M business its easy to understand where you end up on the Model Market Fit graph. But what about before that point? Your Model Market Fit hypothesis revolves around some simple math:

ARPU x Total Customers In Market x % You Think You Can Capture >= $100M

Take the average annual revenue per customer/user, multiply it by total number of customers/users in your target market, then multiply that by the percentage you think you can capture. That should equal or be greater than $100M.

This might seem simple, but many teams I see and advise don't do this. Each variable in this equation has some assumptions, and I recommend thinking through them in this order:

Total Customers In Market

First, define your target market. You should have done this already at the Market Product Fit stage anyway.

Once you have this definition you should do some research on how many target customers meet those criteria. If you find that this number is too small, then you can expand the criteria to target a larger market, but then you need to return to the Market Product Fit step to see if that remains true. You also need to understand if customers meeting the expanded criteria are willing to pay the same amount.

ARPU

After you have defined the market, you can do some qualitative research to understand what their willingness to pay is for your solution to build your ARPU hypothesis.

If you find this to be too low to fit the Model Market Fit equation, then you can think about increasing prices. If you do increase prices, you need to make sure that Channel Model Fit still holds true. You may need to change the definition of the market to find customers with higher willingness to pay.

% You Can Capture

This variable is probably the hardest one to predict. If you have nailed down your target market and know how many target customers there are and you understand what they might be willing to pay (ARPU) you can back into the % of the market you need to capture to create a $100M+ business.

If anything, it is easy to overestimate the percentage you think you can capture. For example, if you are a SaaS startup and this variable comes out to 50%+ then you should be worried.

Instead, for SaaS businesses where there aren't strong network effects, I use 10% as a rule of thumb. Great SaaS companies will capture more than 10% of their target market over time, but this is a good starting point.

Companies with strong network effects can assume a higher percentage because you are typically playing an all or nothing game. If you win, you will probably capture the majority of the market.

Moving from Market to Market

If you've read some of my other material I also typically recommend starting with a niche market in the earliest days and then expanding out.

Often when you use the Model Market Fit equation with the niche market, it never ends up equaling >$100M. That's fine.

In that case, you just need to have hypotheses for what the next expansion markets are and how big they are.

The more times you need to expand to get to a $100M+ business, the riskier your core hypothesis is. Every time you expand there is risk that your four fits don't hold true.

Next up, we'll look at how the Four Fits work together. Look to your inbox for the next installment!