Conflict happens when people care enough to disagree. And your choice to embrace or elude these moments is how you shape your organization’s future.

All organizations develop a culture of conflict, whether or not its leaders have a hand in shaping it. Without thoughtful design, behaviors emerge organically and grow wildly — often replicating the temperaments of founders and leaders.

At an early stage, this may feel like a reasonable issue to ignore. Worrying too much about culture before you have a viable business can feel like putting the cart before the horse. Too often, though, leaders never take that crucial step back to design and model the conflict-navigation behaviors they hope to see. When their companies enter hypergrowth, they’re left with a tangled mess: an unhealthy system that squelches innovation and leads to suboptimal decision-making.

Healthy navigation of conflict is crucial for successful teams, but leaders need a playbook to help their teams achieve it.

Here it is: To develop a productive culture of conflict, you must identify specific behaviors you want to see in your organization, and then embed these behaviors into your team’s values, norms, language, and rituals.

About the Authors:

Katherine Ullman is a strategist and writer. Most recently she was the Senior Director of Organizational Strategy at Paradigm, where she built products and led data and consulting teams.

Natalie Rothfels is an Operator in Residence at Reforge and runs a leadership coaching practice. She has held product leadership roles at Quizlet and Khan Academy and was a classroom teacher before that.

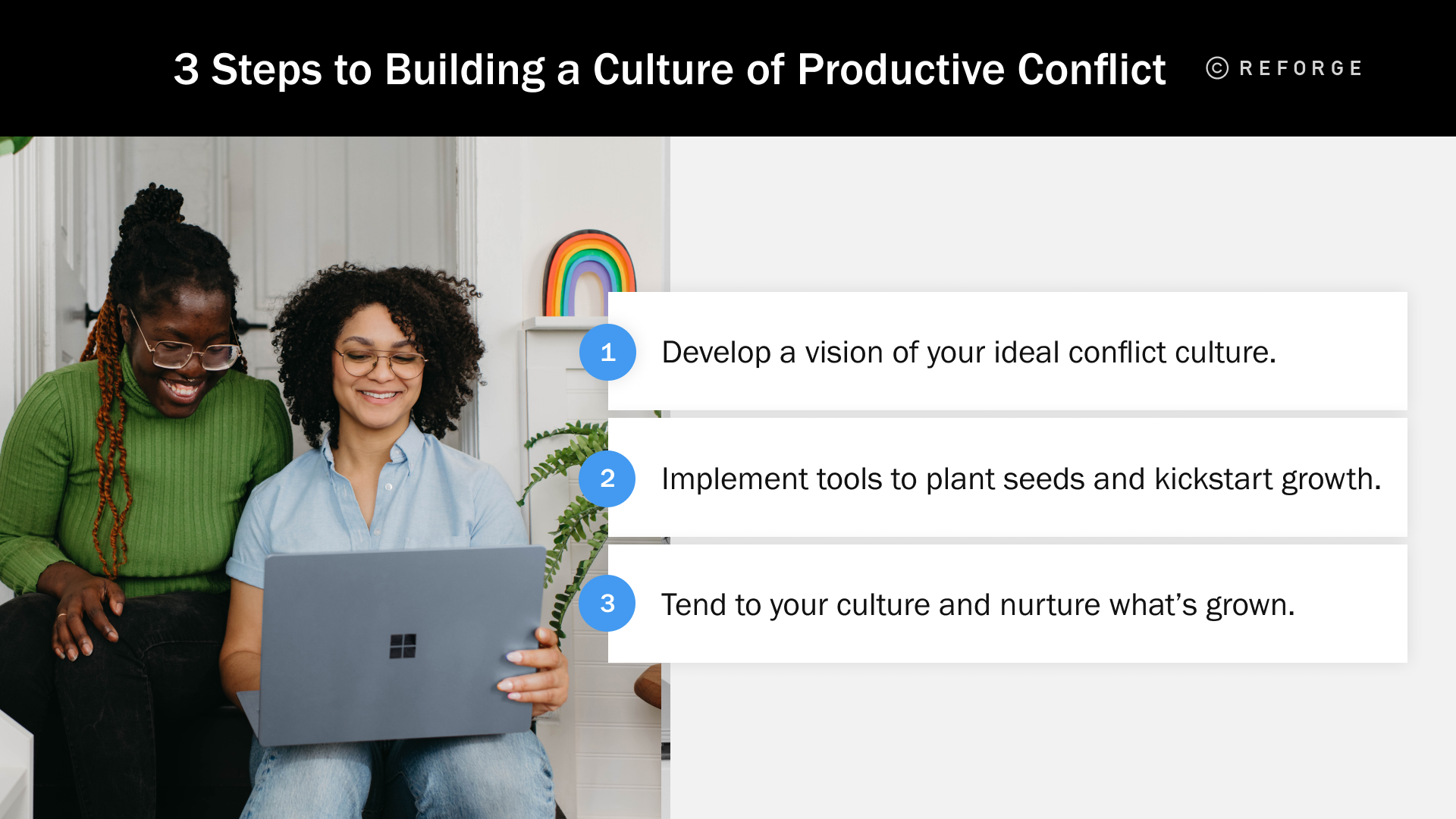

3 Steps to Building a Culture of Productive Conflict

Intentionally creating a culture of productive conflict is not unlike planting and nurturing a garden:

First, you develop a vision for what kind of culture you want to grow and why.

Then, you plant the seeds and kickstart growth.

And last, you tend to what’s surfacing, modifying as necessary to realize your initial vision.

Let’s walk through each of these pieces in turn.

1. Develop a Vision of Your Ideal Conflict Culture

Culture is the norms and beliefs that shape behaviors and tendencies.

Before you can design a culture of conflict, you’ll need to interrogate your own tendencies around conflict. Looking at the stories you tell about conflict will teach you to recognize how your own habits may help or hinder the organization, providing a clearer slate to build a more ideal culture.

Executive coach Loren Bale says that self-inquiry is at the heart of a lot of the work he does with CEOs and their teams.

“All of us have a starting point with respect to how averse we are to conflict,” he says, and the CEO’s attitude “is often what sets the tone within the executive team. Very often that tone is not intentionally shaped. This norm is important enough that it should be discussed, debated, and strengthened through practice.”

In addition to reflecting on your own habits, this vision-mapping moment is also an opportunity to draw on feedback from others, or engage a coach to evaluate how your behaviors are perceived and impact those around you.

For example, a conflict-avoidant leader may over-rely on the “disagree and commit” approach, only to be surprised when innovation has halted and few people are engaging in meaningful discussions. Similarly, a conflict-provoking leader may think that they are engaging in healthy debate only to realize that others perceive them as intimidating or combative.

When you’re ready to engage in self-inquiry, here are some questions you can ask yourself:

What types of conflict am I most prone to engaging in, or perpetuating?

How should conflict operate in this organization in order to reach our goals?

Does this dream design indicate skills that I need to develop, or what bad habits I need to break?

Once you’ve done this self-inquiry work, you then need to partner with your leadership team to determine how you will collectively engage in and model conflict throughout the organization.

One starting point is having each person share what they’ve discovered in the self-inquiry process. You may be surprised to find a commonality: Conflict puts most of us into psychological stress. And when we navigate conflict from a stress state, it rarely pans out as we hoped.

“If you’re not your best self in conflict, it becomes about one side winning and the other side losing,” says Matt Greenberg, CTO at Reforge. “You have to be able to find a place inside where you’re comfortable with the conflict. The best version of you is the person who resolves it.”

Here are some questions you can prompt your company’s leadership team to discuss and align around:

What adjectives describe our current culture of conflict?

What is our collective vision for how conflict ought to operate in this organization?

How have we successfully — if at all — navigated conflict before?

Mis-alignment at the leadership level can lead to unnecessary conflict downstream in the organization, as each functional department develops their own interests and goals that may be at odds with each other.

“When people aren’t actually in agreement about key strategic decisions, it has a lot of damaging effects on performance throughout the organization,” says Nathan Parcells, a former founder turned executive coach who works primarily with co-founders. “Employees get pulled in different directions by different execs, which is frustrating, ineffective, and eventually will lead to churn.”

Leaders set the tone from above. Employees can easily sense the conflict happening at the exec level, according to Nathan, even if it’s never made explicit: “Functional leaders in long-term conflict create fragmented strategies, which then leads to diffusion of responsibility and lack of clear decision-making ownership”

2. Implement Tools to Plant Seeds and Kickstart Growth

With a vision in hand, it’s now time to plant the behaviors you wish to see. There are two valuable tools you can leverage to design a culture of productive conflict: your company’s core values, and shared vocabulary.

Cultural Values

While it’s important that your company’s core values reflect your cultural vision, you shouldn’t aim to scrutinize every behavior for value-alignment. In fact, cultural values need not be explicitly about conflict to shape how conflict happens, according to Jeanette Mellinger, User Research EIR at First Round Capital and former Head of UX Research at Uber Eats.

“It’s funny, the organization I worked for had an external reputation for having conflict being too conflictual, but that wasn’t my experience there at all, in part because we were so intentional about culture on our team,” she says. “I shared a deck with all new employees that laid out our team’s values. None of these were about conflict explicitly, but they made clear the expectations we had for how people should relate to one another. And some of them, like ‘Assume positive intent,’ did have implications for how you might enter into conflict.”

If your company has core values already in place, it’s a good idea to review them with an eye toward conflict and decision-making, as they can inadvertently be weaponized — or leveraged — as your company grows.

For example, values like “Be kind” or “One team, one family” might promote harmony over disagreement. And values like “Ask for forgiveness” might encourage urgency over alignment.

Improve the clarity of existing values if you are concerned they might be used to create a conflict culture antithetical to your goals, or consider embedding new ones to support your vision. Choose wisely; what you plant will grow.

Shared Vocabulary

Beyond a company's core values, shared vocabulary can also support healthy conflict. The leaders we spoke with shared many examples of terminology that they use to encourage core, observable behaviors, like sharing different perspectives, listening with empathy, having difficult conversations, and naming consensus or conformity.

Here are some examples we heard during our conversations:

“Let’s put our bubbles together” (as in, “let’s clarify our different perspectives and assumptions”)

“I want to have a courageous conversation” (as in, “I want to talk to you about something that is difficult”)

“I want to cleanly escalate this” (as in, “I want us to agree to bring this disagreement to a more senior person together”)

When teammates reference shared terminology during a conflict, it serves two purposes: It makes the potentially challenging interpersonal dynamics more explicit and reminds everyone they are still part of the same team.

These dissemination tools — core values and terminology — can be embedded across the organization in onboarding, organizational communications, management training, and process or meeting templates. By doing so, the cultural vision that emerged from executive meetings starts to grow in the organization at large.

Nathan Parcells reminded us that this is a practice, not an end-state. One tool he uses with co-founders to provide structured practice is the 10-15% rule: “I ask people to bring feedback for the other person that’s 10-15% into their risk zone. People need to practice taking 15% risks with their teammates to build shared skills of conflict resolution and a shared awareness that you can get through hard times together.”

3. Tend to Your Culture and Nurture What’s Grown

The three most powerful means for tending a culture are modeling, incentivizing, and redesigning.

Modeling

In almost every interaction, you have the opportunity to demonstrate or model the type of conflict behaviors you wish to see. You can encourage dissent, identify when there’s too much consensus or even nudge teams to disagree in ways that underscore a shared sense of purpose.

Avoid the temptation to solve problems for your reports, and instead provide context that helps clarify priorities.

In one on ones, you can coach your reports on how they might engage in a specific conflict at issue, even suggesting language they might use to express their views or solicit a teammate’s opinion.

When relaying a major decision that emerged from conflict, share its origins, highlighting how different parties shared their perspectives and the process by which you arrived at a solution.

If you’re avoiding tension, create intentional space — and time — to practice conflict resolution with other leaders.

“I see cofounders trip up by practicing in 30 minute increments,” says Nathan Parcells. “You need time. This allows you to get past presenting facts and move towards clarifying the underlying feelings and stories that are involved in the stickiest conflicts.”

When employees escalate a conflict to you, ask questions to clarify the conflict or otherwise support teammates in constructively resolving issues.

Matt Greenberg shared an example with us that underscored the power of effective modeling during escalation.

Two leaders were at a crossroads about how to most effectively organize pods within their team. One advocated for an arrangement that prioritized flexibility, while the other argued for more clear and rigid scopes for each pod. These leaders escalated the disagreement because their views were irreconcilable. It was important for Matt not to determine a solution for them; he wanted the leaders to resolve this conflict on their own so they would feel joint ownership moving forward and be able to resolve future conflicts independently. What Matt was able to provide was an external perspective that reframed the disagreement.

“I realized that they were debating at a philosophical level, not a pragmatic one,” says Matt. “So I didn’t solve the conflict for them, but I gave them the criteria to solve for that would help them break the tie: I encouraged them to commit to a path for a shorter time-frame rather than debating about the ideal team set-up in perpetuity. This lowered the stakes: it’s easy to feel like you’re committing to something permanently when you’re in a philosophical argument.”

Matt shifted the conflict away from the philosophical question (“What’s the best way to set up a team?”) — to a question that emphasized the need to make progress (“What’s a good way to set up the team today, based on what we know, accepting that it will likely change in 3-6 months?”). This was the key that unlocked an otherwise seemingly intractable issue.

Incentivizing

You can incentivize the conflict behaviors you wish to see — and not see — by embedding them into performance management processes across the organization. This creates a recurring opportunity between managers and reports to discuss these behaviors, keeping them top of mind. Reward employees who demonstrate desired behaviors, and coach employees who fall short..

This incentivization will be much more successful if the types of desired behaviors — and the reasons behind why they are desired — are clear to all. Describing these behaviors in core values is one way to do this. Clarifying them as norms during onboarding and manager training is another.

Paying attention to incentives in organizations also entails reflecting on how undesired behaviors may be incentivized unintentionally.

On a regular cadence, leaders should also reflect on how seemingly unrelated incentives may be inadvertently driving conflict behaviors. For example, driven by pressure to move fast, meetings might include too much groupthink and not enough healthy tension. Ask: “What incentives would better enable the culture of conflict you’d like to see?”

Re-designing

Just as product retrospectives are commonplace on development teams, culture retrospectives ought to be commonplace on leadership teams. Sometimes what’s designed has unintended consequences or just doesn’t work and needs attention. That’s fine — there’s no final destination for culture. We always have the opportunity to reshape and tweak as we learn.

Leaders should be on the lookout for signs of ineffective conflict behaviors, and then make sound judgment calls about how to address them.

For example, it’s perfectly normal for teams in different development phases to have different levels of conflict. A more junior leader might fear the conflict that’s so heavily present on teams who are still learning how to collaborate and partner together, the Storming phase. A well-designed culture and effective leader will instead acknowledge the presence of conflict and help a team move through it rather than getting stuck in it.

Leaders can also solicit feedback from their peers and reports about whether their original designs have lived up to expectations. Or, they can identify whether the conditions have changed enough to necessitate a deeper reset (e.g. in hypergrowth companies, the pace of hiring usually far exceeds the speed of onboarding and dissemination of cultural practices around conflict).

It’s a Journey, Not a Destination

There is no end to developing your culture. Successful organizations are dynamic organisms that change and grow.

To handle that, leaders must recognize that building a culture of productive conflict is an intentional practice rather than an outcome.

The next challenge will come, and your responsibilities as leader will shift. Embracing this challenge and increasing your range of comfort with conflict will help you to adapt and grow with rather than apart from your organization.