Organizational conflict is a polarizing topic. Individuals view either its presence or its absence within a company to be lethal.

Proponents of conflict believe that without it, organizations fail to incorporate a diversity of perspectives and lose out on innovative potential. They believe that those organizations are often subject to groupthink, suboptimal outcomes, and occasionally explosive incidents that result from prolonged conflict avoidance.

Advocates against conflict see the ways that it can create cultures of fear, produce constant stalemates, and push many conflict-shy employees to the sidelines.

Both of these perspectives are correct. But adopting a conflict-averse or conflict-provoking culture can lead to malfunctioning organizations.

We believe leaders get better outcomes when they can model and embrace good conflict within their teams.

In this post, we’ll introduce the Rubber Band Theory, a framework meant to help you articulate how conflict operates in your organization.

From there, we’ll debunk what distinguishes good conflict from bad conflict, and share some tools to effectively model and move conflict from one state to another.

Meet Our Authors

Natalie Rothfels is an Operator in Residence at Reforge and runs a leadership coaching practice. She has held product leadership roles at Quizlet and Khan Academy and was a classroom teacher before that.

Katherine Ullman is a strategist and writer. Most recently she was the Senior Director of Organizational Strategy at Paradigm, where she built products and led data and consulting teams.

Doa Jafri is an Operator in Residence at Reforge and an early-stage engineering leader. She most recently built and led teams at Glossier and Thrive Global.

The Rubber Band Theory

We define conflict as a meaningful disagreement laced with emotion. Without a resolution, this disagreement creates more hurdles that must be overcome in order to move towards a common goal.

Because most of us struggle to navigate conflict personally, let alone professionally, many leaders naively try to create conflict-free organizations. This eradication approach fails to account for the benefits of conflict and can breed costly incidents if the conflict is addressed far too late.

To address this struggle in a positive and productive way we crafted the Rubber Band Theory, which illustrates how conflict operates within organizations.

A rubber band’s purpose is to hold objects together using tension. But with too little tension, the rubber band flops. With too much, the rubber band snaps.

This principle is also true in organizations. Teams with too little tension often have conflict-avoidant cultures in which conflict is seen as disruptive and unproductive.

Without the space to spar on key decisions, these teams fail to take ownership and tend to require heavy oversight.

Teams like this bury potential issues and move forward on initiatives they don’t believe in. Shifting priorities and objectives are particularly difficult for these teams, as they don’t have enough trust to navigate challenges together.

On the other side of the spectrum, teams that are too tense have conflict-provoking cultures. In these organizations, conflict is used as a tool to regain power and control.

While conflict-provoking cultures may be seen as places where the best ideas emerge out of a productive battle, those decisions are often influenced by those who fight hardest or smother others.

Both conflict-avoidant and conflict-provoking cultures can lead to similar outcomes:

Homogenous teams where individuals who don’t conform to the group’s approach to conflict fail to thrive.

Teams that end up building products that are great for the business and poor for customers, or great for customers with little upside to the business because one domain (engineering, sales, marketing, product, etc) prevails over all others.

The Rubber Band Theory posits the following:

Conflict is useful when it’s purpose-driven

Overcoming hurdles together is the end goal, whether explicit or not

Stable tension zone can be self-perpetuating

Let’s dive into each of these.

Conflict is useful when it’s purpose-driven

Useful conflict is often referred to as a healthy disagreement or productive discussion in many organizations.

It can be so positive and effective that it doesn’t even feel like conflict, which gets a bad rap. Most people have had this experience, but let’s look at what makes it work.

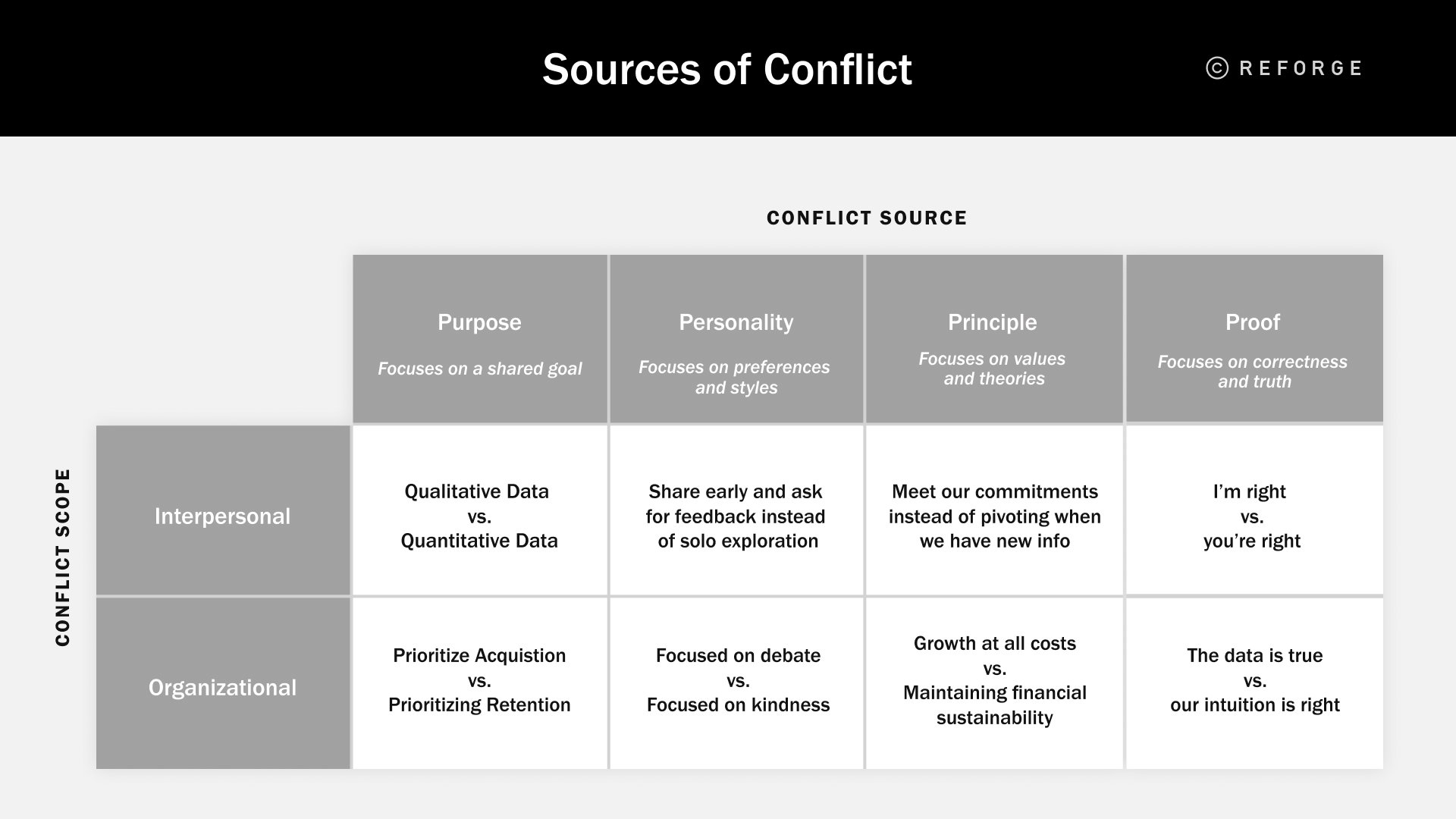

First, there are four types of conflict orientation:

Purpose - “We both want to move this metric but have different ideas for how to go about it.”

Personalities - “I think you’re being disrespectful, you think you’re being honest.”

Principles - “I think we should always go fast, you think we should always prioritize quality.”

Proof - “I think I’m right, you think you’re right.”

Purpose-oriented conflicts focus on a shared outcome that two or more people can agree on, even if they have different approaches for getting to that outcome. These conflicts are rarely about being right, and instead about doing something correctly.

As Buster Benson describes in his book, Why Are We Yelling: The Art of Productive Disagreement, having the right amount of tension can be a superpower if you understand it’s a means to an end.

People who push back against your idea or perspective can be extremely valuable team members because they will help you see any potential blind spots or problems. And avoid investing in the wrong ideas.

On the other hand, personality-oriented, principle-oriented, and proof-oriented conflicts are often zero-sum. They are bred from a sense of vulnerability, scarcity, and the desire to protect.

If there isn’t an explicit shared purpose or enough narrative about how individuals and teams must work together for that purpose to be achieved, people can end up in bad conflict.

We’ll discuss how to move from one orientation to another further in our distinction of good versus bad conflict below.

Get access to the worksheet that accompanies this post! The Sources of Conflict Worksheet can help you track the conflict source and scope once you’ve learned The Rubber Band Theory.

Overcoming hurdles together is the end goal

A rubber band’s purpose is to hold objects together. Similarly, resolving purpose-driven tension allows individuals to move forward together while integrating their perspectives toward a more promising solution.

Approaching conflict with the mindset that it will bring ideas, perspectives, and people together, including strengthening relationships, is very powerful.

It reframes conflict not as a problem with one solution but as an opportunity to generate new solutions that meet the needs or criteria of multiple people.

Loren Bale, an executive coach who works both 1:1 and with leadership teams to improve interpersonal issues, said the belief that conflict can be the basis for strengthened relationships is counterintuitive to many people.

“It can be harder to navigate conflict in environments that are conflict-averse because, as conflict inevitably arises, there are no norms or practices around its potential to be healthy and productive.

“It’s powerful and beautiful to see relationships strengthen through conflict. Individuals that have experienced this in their lives tend to have more tolerance for conflict and comfort with bringing it into their executive teams.”

Stephanie Kwok, an EIR at Reforge and former VP of Marketing at FanDuel, agrees.

“Projects are finite. Relationships are everything and will pay much greater dividends than the satisfaction of being “right” about something or making someone know they made a mistake.”

Stable tension can be self-perpetuating

When conflict is navigated effectively and a relationship is strengthened, most people gain more confidence that future ruptures can actually lead to cohesion rather than destruction.

This sets off a positive feedback loop. You can think of this as a Rubber Band Ball — many scenarios in optimal tension can compound on each other.

Agata Celmerowski believes that this stable tension zone enables Collaborative Intelligence.

“A strong leader doesn’t just optimize for the individual, but for a healthy system.”

Imagine two teammates. Person A is very detail-oriented, scrappy, and risk-averse. Person B is very entrepreneurial, risk-oriented, and focused on taking big swings.

When they team up, Person A will stop Person B from taking on too much work and not getting it all done. While Person B will help Person A take more risks and not be afraid to fail.

Caroline Hollis, General Manager at Square, discovered a similar approach that has made conflict less scary for her.

“A lot of people associate conflict with meaning one party wins, and the other party loses. What you actually want is to find a way for both parties to win.

“You can almost always do that by figuring out what both parties interests are, what the overlap is, and how to maximize that set of interests.

“That helped me get a lot more excited now when there’s disagreement because I see it as a really interesting intellectual challenge to figure out how to satisfy both parties' needs.”

When all parties feel like their needs are getting met, they’re more likely to engage in future conflicts. Especially if it becomes a fun puzzle to work through together!

The three tenets of the Rubber Band Theory — that conflict is useful when it’s purpose-oriented, overcoming hurdles together is the end goal, and the Stable Tension Zone can be self-perpetuating — can be used as a reflection tool for your team to remember the ideal state and source of tension to aim for.

Good Conflict Vs. Bad Conflict

Good conflict lives in the Stable Tension Zone. Bad conflict exists outside that zone, with either too much or too little tension.

In order to support stable tension within your organization, you need to know how to recognize it.

The right type of tension exists when all parties:

Perceive high trust and respect from each other. Low trust environments do not enable psychological safety or honest conversation.

Belief in a meaningful resolution. Fake commitment to a resolution is a great way to tank any relationship.

Explicitly name a common, external goal. When we’re in conflict about something implicit, we fail to listen and understand the other party’s perspective. Becca Shapiro, a Senior Software Engineer at Glossier, expands on this idea, “Healthy conflict has no winner and no loser. It's brainstorming, hashing out ideas, and choosing a direction.”

Sense progress is being made. When things feel stuck and immovable, it’s natural for people to have automatic and usually unskilled stress responses that get projected on the other party.

Have awareness of power differentials. It’s difficult to engage in any conflict when power structures are overt and reinforced. The person with more power must be able to create trust and safety for a productive conflict to exist.

Grow the pie together rather than cutting it. Conflicts get unstuck when people can co-create something. This includes moving towards a decision, revealing new information, creating a new connection, enabling more trust, or generating compelling alternative options. If you’re in a cycle of blame, shame, or confusion, you’re cutting the pie rather than growing it.

“A more diverse group may have more disagreement and conflict, but it’s so important because you’re getting different perspectives that help move towards the best outcome. It’s all about creating an environment where people feel safe to voice their opinion, and then have the tools to work through those conversations constructively.” - Caroline Hollis

Recognizing these attributes is critical because conflict itself isn’t inherently good or bad. It’s how that conflict is navigated that matters.

“You can have conflict that starts for the right reasons but very quickly devolves. When you start anchoring too much on the internal (how you feel) versus external (what you’re both trying to achieve), the conflict itself morphs from something productive into an obstacle.” - Agata Celmerowski

The Sources of Conflict Worksheet can help you track the conflict source and scope once you’ve learned The Rubber Band Theory. Sign up to receive exclusive Reforge content!

How to Move Conflict from One State to Another

If your organization or team suffers from too much or too little tension, it will take conscious effort to move into the Stable Zone.

If the tension in your organization is too flimsy, you’ll need to start modeling and incentivizing tension.

Depending on where you sit within the organizational structure, this can include pointing out when there is too little disagreement, by saying:

“I don’t hear any dissenting voices in the room - does anyone disagree here? If not, what would be the biggest weakness of this approach?”

Or thanking individuals when they do dissent, by saying:

“Really appreciate you pushing us on our thinking here!”

It can also include sharing directly with your reports any recent conflicts you’ve had to navigate, which normalizes the tension as productive.

Now, if the tension in your organization is too strained, you’ll need to exemplify behaviors and approaches that reduce tension.

Here’s how you can reduce, and redirect, tension during conflict:

Understand perspectives and name assumptions

Identify and explicitly name the source(s) of conflict

Generate all possible outcomes

(Re)Establish a shared external goal you both agree on

Clarify the criteria for how you’ll make a short-term resolution

Actually commit to the decision

Understand Perspectives and Name Assumptions

Purpose-driven conflicts are often bred from misaligned expectations or lack of shared context. They still trigger highly-charged emotions because we’re human.

It’s important to first do your own inner work to understand your perspective and the assumptions you’re making so that you can then lay that context on the table and seek to understand the other party’s perspective.

This is especially true if the conflict has shifted into the territory of personality-driven, principle-driven, or proof-driven, rather than purpose-driven.

Remember, purpose-driven conflict in an organization is good.

“Sometimes a conflict may become intractable when it starts touching on an individual’s sense of intelligence or worth. You often have to unwind the conversation to the source before you can solve the conflict itself.

This demands a willingness to reflect on what projections might be at play and openness to examine patterns or painful internal processes that might be playing out in the conflict. That’s hard to navigate within a business context.” - Loren Bale

Once you’re grounded enough to hear context from the other person, you can ask open-ended questions to gather information. Then seek to understand what’s happened from the other person’s point of view.

Stephanie Kwok believes that if you can understand the root cause of someone’s behavior, instead of relying on assumptions, you can open your mind up to their true intent.

Also by understanding the root causes of behavior, you can potentially avoid larger issues in the organization.

Questions you can ask:

I might be missing something. Can you help me understand how you arrived at this conclusion?

What information do we each have that the other might not know about?

How did you experience what happened?

How did you interpret what happened?

Where do you think our perspectives differ?

What’s most important to you about how we (make this decision, clarify the goal, bring other people along, etc)?

What assumptions am I making that are incorrect?

Identify & Explicitly Name the Source(s) of Conflict

Self-awareness is a critical skill for navigating conflicts effectively. You need to first understand the source of the conflict to be able to make progress on it.

Remember that there may be multiple sources of conflict, especially if you’ve let something fester. Though it’s easy to feel like they’re just coming at us, conflict is rarely that spontaneous.

When you name the source, you’re more likely to be able to choose how to engage with it. This is just as important for interpersonal conflicts as organizational ones.

It’s possible for teams or company values within an organization to inherently be in conflict.

For example, you might have teams that represent the needs of the customer whereas others more closely represent the needs of the business.

Or, you might have organizational values that encourage both speed and quality, but, sometimes in order to go fast, you have to cut corners; other times in order to produce high quality, you have to slow down.

Often, naming these inherent tensions can help generate new options or make it clear when you need to escalate to the decision-making for a clearer direction.

Questions you can ask:

Is there a personal value that you have that you feel is getting compromised in this situation?

What’s most important to you about this decision?

Generate all possible outcomes

When we’re under stress it’s common to see few possible outcomes. Conflict often happens when we’re in an environment that doesn’t allow us to imagine multiple solutions at once or come up with a solution that satisfies all parties.

“If you don’t know what the possible outcomes are, you’ll struggle to know if the conflict is truly changeable or not.

If it is, then you can try to understand what inputs will be necessary to drive that outcome, but you’ll still need to decide if the effort required is worth fighting for that outcome or if it’s actually better to just disagree and commit.” - Matt Greenberg, CTO at Reforge.

Questions you can ask:

What do you see as the best possible outcome?

What are you optimizing for?

What information would help you feel comfortable with this decision/approach?

(Re)Establish a shared external goal you both agree on

It’s easy to fast-track a disagreement while totally ignoring what you actually agree on. Focusing on a common externalized target goal can help depersonalize conflict and take the emotional heaviness down a notch.

For example, if two people have competing perspectives at the conclusion of an important A/B test, they may slip into a conflict of proof.

One person thinks the decision should come from what the data reveals. The other person believes that the data itself is faulty and insufficient.

Instead of arguing about which data is correct, it’s better to first establish where they agree: they both want to use credible data to make the decision. They can now focus on how to ensure the data is credible.

Questions you can ask:

What’s the big goal that we both agree on?

Is there something we both need more clarity on (e.g, making an explicit tradeoff decision) that we can escalate up quickly to our leads?

What does success look like to you here?

Clarify how you’ll decide to move forward

A lot of conflict is caused by people disagreeing about solutions rather than anchoring on a shared understanding of the problem. This is exacerbated by the fact that we’re paid to solve problems.

Starting upstream with a shared, clear problem statement and goal, which Natalie refers to as returning to the beginning of the watershed, can reduce information asymmetry because all parties share what context they’re privy to. It also helps folks focus on a shared outcome, which can reorient zero-sum thinking.

Questions you can ask:

What’s the real problem we’re trying to solve?

What criteria will we use to make a decision, knowing there’s likely not just one right one?

What information might we be missing that would help each of us move forward?

Actually commit

Disagreeing without committing is pulling the rubber band so tight that it’s likely to snap.

On the other hand, agreeing but secretly not committing sabotages the decision, leading to a loose rubber band.

“It’s not feasible to be in conflict with everyone all the time. You won’t get anything done. Long-term disagreement is a drag on any objective.

It generates a lot of wasted energy, and in most organizations, time and energy are the most valuable currencies. It’s amazing how much positive energy you can get by actually committing and moving forward.” - Matt Greenberg

Questions you can ask:

What would each of us need to do in order to disagree and commit?

What does commitment actually look like for each of us?

Is one of us disagreeing and committed much more often than the other?

Conclusion

Like many facets of organizational life — speed, professionalism, process — there is an optimal state of conflict needed to support the outcomes most important to you.

We believe there is something valuable - and radical - in accepting that:

All of us will face conflict at work, whether we are in conflict-avoidant organizations or not.

Conflict, when approached in the ways we have described above, has the ability to reshape organizations. It is an engine of innovation and of change.

But this is not an easy feat; turning conflict into something useful requires a shift in mindset, behaviors, and culture.

To start making this shift, identify a conflict that currently hinders your ability to effectively make progress against your goals. Then, use this Sources Of Conflict Worksheet to reflect on the source of your conflict, and commit to one action to usher it from bad conflict to good.

Sign up to receive the Sources of Conflict Worksheet that you can fill in once you’ve finished reading The Rubber Band Theory post!