Erika Warren is a Reforge EIR on Retention + Engagement. She's the former VP of Product & Strategy at Wyzant, a tutoring marketplace supporting millions of students with their learning goals. Before Wyzant, she was a founding member of the Grubhub product team.

Behzod Sirjani is Reforge Partner who created and leads User Insights for Product Decisions. He also founded Yet Another Studio, a research practice helping people bring rigor to their curiosity. Previously, he did research at Facebook and was the Head of Research & Analytics Operations at Slack.

Ravi Mehta is a Reforge EIR - he created Product Leadership and leads Product Strategy. Formerly, Ravi was the Chief Product Officer at Tinder, Director of Product at Facebook, VP Consumer Product at TripAdvisor, and Product at Xbox.

Keya Patel is an OIR at Reforge. Previously, she was the Director of Product Growth at Headspace and a Product Manager focused on Growth & Monetization at Dropbox. She has expertise in the subscription space across B2C and B2B.

Tech leaders need to focus on business value above all else, which includes what's best for a user and what's best for business growth. How to balance the two (user & business) is one of the most pressing questions in tech. At Reforge, we see this question asked in a variety of ways:

Is it possible to prioritize our customer's needs and grow rapidly? Why does it feel like a tradeoff?

What do I do if my team needs to hit our metric, but we're losing sight of users' feedback?

What best practices (and ethical guidelines) should I consider as my team builds a habit loop?

Why don't we talk about the negative consequences this product change could cause? We keep focusing on the best-case scenario.

Even outside of the product world, these questions have surfaced in mainstream news with Netflix's 'The Social Dilemma', Facebook continuing to be scrutinized for user trust/privacy related reasons, AI models demonstrating bias, and Big Tech fighting international regulatory battles.

Let’s answer one of the most pressing questions in tech

In this piece, we'll break down how to address the challenging user/business tension, through five key investments you can make. The investments begin with gaining an increased understanding of this tension, before moving to actionable next steps to take within your organization:

We’ll start by looking at some well-known examples of where business value and user value clashed. The line isn’t always clear and even well-intentioned product leaders can end up optimizing for one at the expense of the other.

Next, we’ll see why it’s so important to get this balance right. As competition increases, companies cannot succeed in the long-run by optimizing for themselves at the expense of the user.

Then, we’ll do a deep dive into the most famous example of unintended consequences — the time spent metric. Early on, Facebook optimized for time spent, and assumed their company mission to connect people was aligned with wellbeing. But, Facebook ultimately found time spent was not a good measure of user value, and has gone through a challenging process of understanding how to strike the right balance for its users and its business.

We'll follow up with how the relationship between user value and business value is not static during company growth. At the seed stage, companies need to focus almost entirely on user value — that is how they can create something which breaks through existing incumbents. As companies grow, they need to reconfigure that balance. We’ll discuss how to strike the balance at each stage of company growth from startup to to Series D+.

Finally, we’ll provide a set of tools so you can put these concepts into practice in your own organization. Tech leaders face the difficult task of solving for the user while building value for their companies. This work isn’t easy, but it’s critical for your company, your career, and your impact on the world.

A blurry line: what's best for the user, what's best for business metrics

There are situations where:

It's not clear if a product tactic is what's needed for a user to find value with a product, therefore, helping business metrics

Or, it could be that the feature/decision crosses the line and is frustrating, wasting time, or even harming the user — consequently hindering company metrics

Examples from Clubhouse, Snapchat, and Booking.com illustrate just how undefined this line can get.

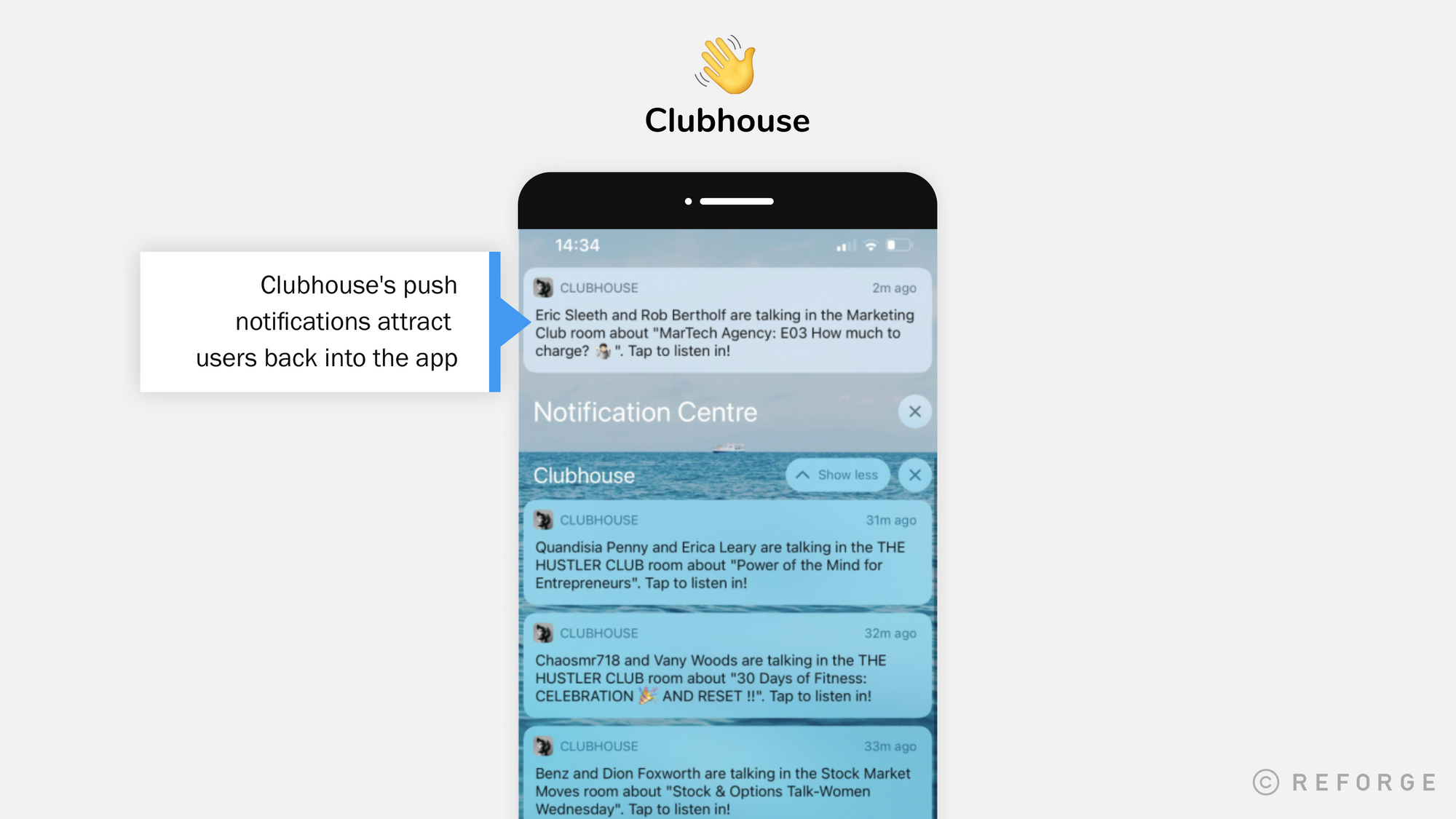

CLUBHOUSE - push notifications

Example: Clubhouse's push notifications that attract users back into the app

This can be best for the business and user when the push notification is contextual to an event starting or letting a user know someone they follow is speaking. In the moment, the user opens up the app to check out what's happening.

Notifications can start to annoy a user if they receive too many in a short period of time — even if they are helpful triggers given the live/synchronous nature of Clubhouse. It could even cause a user to disable notifications entirely (what's best for the user in that moment) and subsequently harm the business since use of notifications is a primary way to get users to re-engage with the app.

Other examples where over-reliance on notifications could be helpful or harmful include:

dating products, like Bumble / Tinder, encouraging FOMO by notifying users that there are a high number of people currently swiping and better chances of a match

dieting products, like Noom / MyFitnessPal / WW, sending daily (or more frequent) reminders to log a meal in order to make progress towards health goals

SNAPCHAT - streaks

Example: Snapstreaks are where a user and a friend have Snapped photos / videos to one another within 24 hours for more than 3 consecutive days. In the app, this is marked by a 🔥 emoji along with the number of days of the streak.

A Snapstreak can be best for the business and user when it's used as a way to foster tighter relationships. This can encourage friends to interact consistently to keep one another updated on what's going on in their respective lives.

But, most people use Snapstreak in a vacuous way, getting little social value for the act of keeping the streak going while also feeling burdened to continue the streak. Some users even take a picture of the ground or the ceiling to keep a streak going. Streaks then feel low value in terms of what's best for a user's time in comparison to just catching up with the friend through any other means or platform.

Other examples where streaks, and leaning into the psychology of not breaking a pattern, may be helpful or harmful include:

fitness products, like Apple Watch Rings / Strava training log, motivating users to exercise daily and visualize their effort compared to friends or previous days

learning products, like Duolingo / Lumosity, aiming for users to come back every day to learn and complete lessons or training

BOOKING.COM - urgency messaging

Example: Booking.com leans into urgency messaging by drawing a user's attention to a limited number of rooms left

Urgency messaging can be best for the business and user when a user is looking to purchase something soon and the business is acting in the best interest of the customer to tell them how many options are still available, so a user can make a decision before their options get booked by someone else.

The flip side is that urgency messaging such as "only X rooms left" or "85% of hotels are booked for your dates" starts to wear on users when they constantly see it across all options on the site, making them doubt the accuracy of information. They may also make a rash decision — booking an accommodation that really isn't the best fit for them because they felt compelled to do so out of a fear of losing out. Or, they could feel defeated about their trip and altogether forgo using the product or change their plans — causing a reduction in business reputation because they're overwhelmed by the presentation of information.

Other examples where urgency messaging may be helpful or harmful include:

email campaigns and sales, especially during holiday periods, where users only have X days before the holiday and end of the sale

marketplaces, like Etsy / Amazon / Facebook Marketplace, where they show the number of people looking at the same item, saving the same item, or items left in stock (all tap into a scarcity mindset)

Teams incentivized by metrics will move metrics. They won’t address user pain points.

It's not apparent that Clubhouse, Snapchat, or Booking.com incorporated a people-first perspective during the initial stages of ideating each tactic — let alone considered what happens when user behavior doesn't play out as expected.

It's much more evident that each tactic mainlines to a metric:

Clubhouse, push notifications → retention metric

Snapchat, streaks → repeat daily engagement metric

Booking.com, urgency messaging to purchase → monetization metric

Teams that are structured and incentivized by metrics often come up with these types of goal-chasing tactics because they are asked to move the needle on metrics. They are not being evaluated on addressing a user pain point or need. We'll talk in much more detail about business-first and user-first metrics later in the article, when we deep dive into the 'time spent' metric.

Companies that optimize for themselves (at the expense of the user) are less likely to succeed

In the short-run, orgs can extract business value at the expense of user value and are incentivized to do so (by revenue targets, funding raises, investor / competitor pressure, usage metrics over value metrics, etc). This can last months or even years, but eventually these companies get disrupted. But, in the long-run, business metrics always follow user metrics.

There are two factors at play that prevent orgs that optimize for themselves (in the short-term) from succeeding over the long-term:

Pace of disruption is increasing

Consumers are becoming increasingly more tech savvy

Pace of disruption is increasing (think Warby Parker and 👓 industry)

Companies that optimize for themselves, at the expense of the user, are prone to disruption. This has always been true, but the pace of disruption is accelerating. Companies like Warby Parker, Casper, and Simplisafe disrupted industries that had been static for decades. The disruption came not just because incumbents were technologically behind and prioritizing their stability/revenue over user value, but also because disrupters used technology to deliver a wholly user-centric experience.

The pace of disruption is accelerating because of (a) technology development and innovation and (b) the amount of capital going into VC backed startups. Even if you look at a software-native section like Human Resource Management, the pace of disruption is getting faster with orgs like Peoplesoft, Workday, Gusto, and Zenefits.

People are becoming savvier consumers of technology

In addition to the pace of disruption accelerating, people are becoming savvier - and more skeptical - consumers of technology. They've gotten used to the customer-first approach of companies like Zappos (with unparalleled customer service) or Airbnb (with their product/design approach to embed customer delight in every moment). As a result, customers have grown wary of privacy, safety, and well-being concerns of companies optimizing for their bottom line over delivering user value.

The principal example here is Facebook. Facebook had a massive social advantage as a moat, but even their moat wasn't deep enough when the company prioritized business value at the expense of user value. Trust of the product deteriorated in 2017/2018 onwards as the company:

prioritized and increased ad placements (increasing revenue)

played a complicit role in letting misinformation spread (increasing product engagement)

allowed privacy and security breaches - like 3rd party access to harvesting user data, tapping in to device info, and more

Users started to migrate away from Facebook to Snapchat, Discord, Tiktok, Twitter, and even other Facebook Inc. products like Whatsapp and Instagram. These people sought out experiences that better aligned with their values as well as businesses that prioritized the user.

Durable business value comes from meeting customer needs

In the long-run, if a business invests in building user-value and operates with a user-first perspective, business metrics will follow. But, some companies, due to their market power or differentiation, have had windows where they could extract value at the expense of the user. Those windows are closing. Startups are, and continue to, rush in and provide alternatives. Users are astute and abandon products that don't serve them well.

In some more extreme cases — with Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon — market power can be so high and users have nowhere else to easily go (due to cheaper costs, ease of use, ecosystem switching costs, etc). Meanwhile startups get crushed or bought out if they try to compete. In those situations, governments have started to more actively strip away market power through breakups or regulatory action.

Deep dive: the 'time spent' trap

A prime example of what happens when centering a business-first metric played out with Facebook creating and using the 'time spent' metric. This metric is still used across tech products to promote the overall time a user spends using a product. In this deep dive, we'll cover:

Origins of the 'time spent' business metric

Pitfalls of the metric

What happens when others copy 'time spent'

Moving to 'time well spent' to start considering the user first

Time as the only constant at Facebook

Facebook mentioned using the 'time spent per person' metric in the Q2 2013 earnings call. This metric was selected because:

Facebook had so much surface area across messaging, newsfeed, marketplace, photos, etc that instead of adding up disparate metrics from each area, the team looked for a unifying and equalizing metric. And, time was the only constant. By focusing on time, and observing/increasing time spent, Facebook could better quantify new feature metrics, engagement levels, or long term retention - all in relation to the time a user spends with Facebook.

Initially, spending more time on Facebook was seen as a good, if not great, thing. This aligned directly with Facebook's mission of making the world more open and connected (where spending more time on Facebook = creating and nurturing connections).

More specifically, during the Q2 2014 Facebook earnings call, Zuckerberg implied that the more time a user spends with the app, the more room to grow the business:

"One thing that’s exciting is that there is still so much room to grow. On average, people on Facebook in the U.S. spend around 40 minutes each day using our service, including about one in five minutes on mobile. This is more than any other app, but overall people in the U.S. spend about nine hours per day engaging with digital media on TVs, phones and computers. So there is a big opportunity to improve the way that people connect and share." -Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook CEO and co-founder

Pitfalls of the 'time spent' metric

But, there were a few main issues with using the time spent metric:

Number of hours in a day

Assuming a winner take all situation

No definition of quality

Number of hours in a day

With time spent, there is an automatic pitfall of only having a finite amount of time — 24 hours in a day. By focusing on time/hours, the prioritization is on a usage metric over a value metric (of providing the most value in this very limited about of time). The org is then automatically going try to monopolize a user's time. The org may not have malicious aspirations, but does this because it's easy to measure, comparable, and usually what's bringing in revenue in one way or another.

Why is number of hours a pitfall?

Org/Product is incentivized to 'steal' as much time as possible

It assumes (more) time spent is automatically a good thing, instead of value or increased efficiency being a good thing. More specifically, there's an important distinction here between the role of the product as a utility versus for entertainment:

UTILITY Product

Delivers value when it saves you time

As in, you get the utility for efficiency, or less time spent

Example: You need to cook a vegan recipe for a friend and you find a YouTube video to follow a new recipe, instead of spending hours thinking about ingredients and preparation on your own

ENTERTAINMENT Product

Delivers value when you spend your time

As in, you get more entertainment for more time spent

There's usually a point at which "entertainment" products suck up time at the expense of the user's well-being

Example: You're looking to unwind at the end of the work day by watching TikTok videos, only to realize a couple hours later that you haven't been amused by any of the last 4 cat videos you absentmindedly watched

Assuming a winner take all situation

When using the time spent metric, an organization defaults to wanting a user to spend all their time with their product instead of other alternatives. This assumes the competitive landscape is always a winner take all situation where a single product will come out on top (as the majority monopoly) and therefore can dominate all of a user's time. In reality, most markets have multiple players to tap into, as well as nuanced and differentiated audiences and use cases.

Why is the winner take all assumption a pitfall?

When an org believes they have to win by occupying all of a user's time, they also assume there will be an increase in business/monetization opportunities by occupying that time. While you might believe someone can spend all of their time using your product, we can guarantee that's not healthy or what they want. And, this causes diminishing returns, where a user no longer views the product as valuable.

Going back to utility vs. entertainment products:

if I'm using YouTube for vegan cooking videos, I'm trying to get utility and therefore less time = more value

if I'm watching TikTok videos for fun, then more time = more value until there's a point of diminishing or declining returns

No definition of quality

In the definition of time spent (the average time a user spends with the product each day) there is, very obviously, no emphasis on the quality of that time spent. The quality piece helps compile a picture of if the user finds satisfaction in using it, would recommend it to others, or would return to the product in times of need.

Why is 'no definition of quality' in the metric a pitfall?

There is no meaningful or positive user interaction/output tied to a user's time with the product

With a utility product - Time spent can help you see where people are potentially getting value or getting stuck. For example: is a user able to learn a new skill and now wants to invest more in learning? Or, are they getting lost and not accomplishing what they came for? You will need to talk to users to find out, since the time spent metric can't help you identify which is which (getting value or getting stuck).

With an entertainment product - Yes, it's clear that people are using the product if time spent increases. But, it's not clear how they felt from the time they spent — was it a waste, fine, good, or great? For example, the game industry uses the terms "grinding" or "farming" when players spend time in the game because they feel compelled to pursue a goal, not because the time spent is truly fun/entertaining

User value (as measured by quality interactions with the product) is not at all measured or understood.

This results in little to no knowledge on how to build positive user value for the longevity and continued growth of a company

Moreover, this focus can create a (wrong) micro-loop where employees look to reinforce user behaviors that drive time spent, instead of behaviors that drive user value over time

When other companies try to copy time spent...

While Facebook introduced and prioritized the time spent metric, other organizations of varying sizes tried to imitate Facebook's example. Even now, after Facebook has moved away from that metric, other companies still try to see if 'time spent' can work for their business model.

The crux of it comes down to thinking that more is always better — meaning more time spent in the product will always be better for business metrics. The thinking largely comes from how companies monetize, by having more opportunities to display ads, paywalls, or what's free vs. paid when they have more of a user's time. But, there's a breakdown in product and user limits with time spent such as:

At Wyzant, a marketplace that matches tutors with students...

Time spent can't scale to be all hours of the day since students cannot be tutored constantly

And, measuring based on hours of tutoring does not account for quality of instruction and educational outcomes students get out of the time

At Headspace, a mindfulness app...

Time spent won't scale because users cannot engage in mindfulness activities throughout the whole day.

Additionally, it's hard to easily quantify and recognize health benefits from minutes a user spends meditating — this is especially true for new users starting a meditation practice, who want to see immediate results.

At DoorDash, a food delivery service...

Time spent doesn't make sense because a user will only come to the product for a specific use case (wanting to find and pay for food to then be delivered to them)

DoorDash can't create new core use cases to increase a user's time within the product

And, even if they could, should they be optimizing for users spending more time within the product or faster time to ordering/receiving high-quality food?

Each person has their own ceiling with a product. While this might change over time, interaction with a product/experience is intended to be a part of someone's life, not their whole life.

At any tech company using DAU, WAU, MAU...

More generally, almost every tech org parallels Facebook's time spent metric through using an Active users metric (Daily/Weekly/Monthly Active Users). In many situations, 'active' is not thoughtfully defined with a meaningful output from the user perspective. Active is instead defined as a business metric, similar to time spent.

To illustrate, for the New York Times app, Daily Active Users could be defined as:

Users who app open in a day. In a way, this parallels time spent because it's unclear if a user received positive outcomes from opening the app.

Users who click/start an article in a day. This starts to show quality of time spent, in that the user found a NYT article that may be interesting enough to read and learn more.

Users who complete/read an article in a day. This shows even higher quality of time spent within the NYT app, in that the user found a piece important enough to read to completion.

Starting to think user-first: time spent → time well spent

Within a few years, Facebook realized optimizing for overall time a user spends with the product does not necessarily indicate a positive outcome from the experience. As a result, since user value was uncertain, the business value was also uncertain.

Questions arose around what types of interactions cause people to feel better versus worse. For example, with short videos and Facebook Groups:

Short videos

Automatically increased time spent if a user watched a 4 minute video, although the video may not have even been meaningful to the user

Viewing the short video gave 4 minutes towards Facebook's time spent metric, but the user was likely getting low value out of watching the video

Facebook Groups

A user might take 1.5 minutes to quickly respond to a question in a Facebook Group related to their interest in Jazz

Ultimately, they spent less time on the Facebook Group compared to watching the short video, but this Facebook Group interaction was more meaningful and cultivated a sense of community for the user

The 1.5 minute group interaction also tied to Facebook's time spent metric, but the user was getting far greater value out of the community interaction

Questions and research around what impacts a user's well-being caused Facebook to evolve from time spent (more business-oriented metric) to time well spent (more user-oriented metric). And, it was important for Facebook to understand what 'well spent' actually meant from a user value point of view. There were significant efforts to survey users to understand what correlated to increases and decreases in well-being in terms of time well spent.

This is not to say Facebook comprehensively understands time well spent, but demonstrates how the company attempted to move towards user value (versus staying cemented in purely usage/revenue value). In this example, Facebook acknowledged that continuing to use time spent was not an accurate representation of user value and longer-term business value.

What business value looks like, across stages of company growth

In this section we'll cover:

the 3 actors in business value

traditionally, what business value looks like

what successful business value should look like

3 actors in business value: user, culture, ¥$£

💎 USER VALUE

User value = how a product goes about solving for a pain point without causing unnecessary or harmful side effects.

Beyond that, user value emphasizes user satisfaction/sentiment (quality of experience), understanding audience types and segments, and research cycles involving Jobs to be Done and design thinking.

🎨 COMPANY CULTURE

Company culture = intrinsic or explicit beliefs that the organization holds and follows.

This could include areas such as the mission of the org, company values, how team members prioritize initiatives and deal with disagreement, or the shadow of a leader (discussed in the Rethinking Your Operating Cadence blog piece).

💸 FINANCIAL POSITION

Financial position = how a for-profit business chooses to balance their portfolio of assets, liabilities, and equity as a result of serving their customer(s).

This includes validating a product has fit in market to later be monetizable, building a viable business model, investing in several revenue-driving features, reevaluating revenue streams, reporting on user engagement/activity that ties to revenue, cutting costs, becoming/staying profitable, and more.

What people commonly think business value looks like as a company scales...

Startup to Series A

In the early days, there is really nothing to optimize for other than the customer to establish product market fit.

Pre-seed to Series A opportunities exist because bigger companies have a gap in their offering. At this stage, the only way to win customers to a startup is by being better in terms of experience and value/quality.

In addition, the incentive structures are aligned — at big companies, there are many internal measures (hitting revenue and margin targets) that drive incentives and make companies self-serving. But, at seed startups, the incentives are clearly aligned with delivering customer value to reach product market fit.

This is also when company size is small enough that culture is being reinforced by the founders and first 30 employees and internal metrics are around customer focus and innovating rapidly.

Series B-D

The company starts to secure larger amounts of VC funding. Along the way, the org moves to analyze opportunities to improve their financial position.

The company establishes a solid and stable business model to make money.

There is still clear emphasis on the user and company culture, but (internally) it starts to feel like there is a growing emphasis on financial condition to prove business viability.

Additionally, more money means opportunity to acquire and gain more users and increase adoption of the product. This results in diverse and peripheral users with newer use cases and needs, compared to the initial core user in the startup to series A stages.

Focusing on the customer becomes harder because it's not always clear which segment or use case should be prioritized.

The company often then starts to focus on average usage metrics and revenue metrics, since those can be easier to quantify and grasp.

Series D+

The company is seeking exit opportunities or looking to be stable/predictable from a growth perspective. As a result, companies over-index on financial position.

At this stage, the employee size is likely much larger and initial tenants of company culture have worn off.

With scaled orgs, there are now many more internal metrics in place that highlight hitting revenue targets and specific margins. This can causes the majority of employees to think in self-serving way to the company vs. the user, especially since employees are recognized and promoted against these internal metrics.

...and what business value should really look like while a company scales

Compared to the previous visual, this one shows what business value should look like as an org grows. Two significant differences include:

User value (in dark green) is consistently the majority. Optimizing for customer needs, new audience segments, user research, and customer feedback is emphasized across stages of company growth.

Financial condition (in blue) does not grow as drastically as the org scales. This is because over the long-run, business metrics always follow user metrics. So, instead of swinging to emphasize financial metrics, as companies traditionally do, it makes sense to properly emphasize user value internally.

Putting it into practice: applicable tips for user-focused decisions

We've covered how optimizing for business metrics at the expense of users will ultimately hurt a business (through examples from Clubhouse, Snapchat, Booking.com, Facebook's time spent metric, and other factors at play like pace of disruption & people becoming savvier). Now, we'll go through hands-on tips to put prioritizing user value into practice through:

Starting with you

Building your (individual contributor & operating team) toolkit

Building your (leadership) toolkit

Instead of just creating ethics roles and rules, start with you. Yes, YOU!

Product managers and marketers have the power to create and change user behavior. Because we've taken this power for granted, with little to no repercussions, the sense of trust and responsibility in tech has eroded — especially at larger tech orgs.

As professionals responsible for shaping the current and next generation of user behavior and technology, we need to think about our ethical obligation to build value for our products without causing harm. By pursuing this obligation, organizations will then inherently increase business value because they consciously and consistently strive to act in the best interest of a customer.

Ethics comes into question because of power (money) imbalance in the VC backed tech world. It's not at all an easy or feasible thing to change, but there are still things we can do at an individual level. This isn't new thinking. Ethics within business has existed for many years. Doctors, lawyers, financial advisors, and real estate brokers participate in ethical training. For these professionals - exams, licenses, or pledges related to ethics helps manage public trust.

Even within the marketing field, ethical considerations around advertising, messaging, and accuracy are common practice. As the landscape between marketing and product has blurred, product and engineering fields have been behind in the conversation. Right now, the topic of tech ethics in products and experiences largely falls on designers and AI ethicists to lead the conversation. We should not just be relying on new jobs, roles, and regulations in the tech world, but also be adding the right tools to our own tool kits.

Build your (individual contributor & operating team) toolkit

Three ways to begin building your own toolkit to prioritize user value for business value include:

Incorporating consequences into planning and development

Correcting for metrics and evaluation criteria

Getting varied feedback from customers

Incorporate consequences

Some ways to avoid (or at least acknowledge) consequences that may come up is to actually consider them during the product development cycle. This can take the form of:

Red teaming it

Holding pre-mortems

Thinking through Maslow Mirrored

Creating a consequences short list

RED TEAMING IT

Red teams are used in security, military, and intelligence to act as enemy or opposition. These teams serve the purpose of getting feedback from the opposing perspective to better their own processes.

With this tool, you would be looking to play the role of a weary user or even an ethicist. You can also ask a peer to play this role instead, since they could bring fresh eyes.

In this role, poke as many holes as possible into the current feature setup and think about what could be wrong from the user's perspective and from the well-being/satisfaction perspective, which would subsequently hurt the business

Then consider the future problems might arise with the current product initiative

With this list of information, you can go back to your team to see if tweaks should be made to better the user experience.

HOLDING PRE-MORTEMS

Prior to kicking off an initiative, meet with cross functional team members to consider everything that can go wrong and how this initiative could fail. Pre-mortems typically focus on what can go wrong for the product, feature, and business.

In this pre-mortem, consciously spend half the time thinking of consequences to the user and larger physiological, behavioral, psychological, accessibility, or discriminatory implications

This could also entail understanding what's the spectrum of worst case to best case in terms of impact to the user

Then, as the product/feature is built out more, reflections from the pre-mortem should be revisited at sprint retrospectives and milestone checks before shipping

THINKING THROUGH MASLOW MIRRORED

As described in Design Ethically, Maslow Mirrored is an exercise to brainstorm the positive and negative aspects of a product or feature related to each tier of Maslow's Hierarchy of needs: Physiological, Safety, Love, Esteem, Self-Actualization, and Transcendence. Think through each of these areas from a user perspective to push the boundaries on what might be unintended results of product changes.

CREATING A CONSEQUENCES SHORT LIST

Similar to how teams have QA checklists or launch guides, a consequences short list should also be developed and refreshed a couple times a year. At the very minimum questions could include:

How does this feature/product make users feel? What evidence do you have for this?

What impact does it have on others? the environments/communities people live in? marginalized groups?

Who is not using or able to use your product and why?

What ethical questions have competitors faced? If you don't have competitor intel start with: what psychological/behavioral areas does this feature/product play into?

Correct metrics and evaluation

As mentioned in the time spent metric deep dive earlier in this article, it's easy to optimize goals for usage/revenue over user value. Some ways to correct this include:

Picking the user-first metric

Defining how to identify bad behavior

Determining steps to take when an individual or team finds bad behavior

PICKING THE USER-FIRST METRIC

Consider the rationale behind metrics you are setting with your team on a quarterly basis. Is the rationale solely rooted in business success (revenue, margins, usage)? Are the majority of metrics your team monitors on a daily/weekly basis quality (user-first) metrics? Are there any quality metrics in place? If you're looking for a place to start, try with understanding these questions from a user's perspective through qualitative research:

Is the product / feature something I choose to use or am compelled to use, by necessity or habit?

After using the product, has my sense of well-being (or satisfaction) increased or decreased? How so?

DEFINING HOW TO IDENTIFY BAD BEHAVIOR

Similar to fraud monitoring and abuse on the ops and security side, defining how to identify bad behavior can also be utilized for well-being and user behavior. Ideas can come from the previously mentioned red team or pre-mortem. In this process you should define:

What does a poor user experience with high engagement look like

What does a good user experience with high engagement look like

What does a good user experience with low engagement look like

By defining these areas with attributes / metrics to monitor, your team will then be able to understand how to track these users in data. From there you can add it as a new segment (segments could include: power user, core user, casual user, active unsatisfied user). The last segment will be masked within the power user or core segments if quality of interaction is not a component taken into account. And, if you don't have a way to measure quality or outcome, this is the time to consider adding it. It's especially helpful in products that monetize off of something other than the primary customer value, where incentives are misaligned (think ad networks, subscriptions services that don't line up with core value, etc).

DETERMINING STEPS WHEN AN INDIVIDUAL OR TEAM FINDS BAD BEHAVIOR

After defining bad behavior, now it makes sense to determine next steps. Some suggestions include:

Don't sweep it under the rug, surface it to team members and others so they're at least aware of the potential user conflict. From there, you should discuss how to break down the issue to solve.

Although this might seem unachievable to do at first, know that engineering teams have been doing this for years with complicated security, data, privacy concerns, and related incidents

Build new monitoring to determine if this 'bad behavior' is systemic or a one-off

If it's a one-off, it could make sense to build an informal incident response system similar to development team practices

If it's systemic, it makes more sense to follow the first bullet point in this section

Get varied feedback from customers

In most customer surveys, we seek feedback to broad, open-ended questions. Questions consist of some form of: What do you like about this product? What don't you like about this feature? And, what's the top thing you would change?

These questions work for a zoomed out sense of perceived user value, but it's also important to ask more pointed questions to understand long-term effects and value, such as:

How did you feel, from a well-being perspective, when using this product? Can you map out the feelings and moments you had at different points?

What types of issues do you imagine could come up in your life if you kept using this product the way you do? Under what situations would these issues arise?

The goal with these tools is not to slow down or solve for every potential consequence. However, becoming aware and acknowledging the positive and negative impacts our products and actions have on users goes a long way in ensuring your business is keeping user value, and therefore business value, at the front and center.

Building your (leadership) toolkit

We've gone through building your toolkit on the individual contribution and operating team level, now here are suggestions on how to approach this at the organizational and leadership level:

Culture of user value and scrutiny

Invest in training as a reinforcement

Culture of user value

Foster an internal org culture that supports and rewards valuing the user and scrutinizing what could be better. Some ways to approach this include:

Create an anonymous survey, Slack, or physical/virtual box for employees to submit product, engineering, design, data, research, and marketing concerns that might be ethically contentious

Hold workshops to reflect on the top submissions so employees are aware of the challenges and feel part of the solution

During product demos or all-hands, showcase and celebrate where teams made tradeoff decisions that exceptionally emphasized user value and addressed doing no harm (side benefit: this could organically become a talet driver or marketing/PR goodwill)

In candidate interviews, ask questions to probe how a candidate might approach challenging business value questions. An example: in a past role, can you talk through a situation where you had to weigh customer feedback with pressure to grow the business? where did you make the wrong (harmful) decisions for the user in that process and what did you learn?

Outside of the person who runs design research and customer support, nominate an exec sponsor who consistently asks about the voice of the user in business reviews, leadership convos, and board meetings.

Gut check when do you and employees choose to not recommend the product to friends. Why does this happen and what are ways to address this?

Invest in training as a reinforcement

It's important to reinforce an emphasis on user value in different ways for it to be normalized across an organization. One way might be through adopting some of the internal rituals mentioned above and another way might be through external opportunities like:

Allow employee training or learning budget to go towards this topic. This could even include giving permission to team members to use working hours to take classes or watch content around user value and ethical decision making in tech.

A few examples of classes or content: Data Science Ethics through EdX, Ethics of Technological Disruption through Stanford, CEET certification, HmntyCntrd, Hack4Impact ML Systems as Tools of Oppression

Invite a peer from an external org to share their best practices and challenges with a similar feature or industry.

This work isn't easy, but it's critical

Working to emphasize user value while balancing financial/business growth is not easy. But, it's integral for those who want to build sustainable businesses, since businesses that last are ones that serve their customers. It’s also critical for your career, the users/behaviors you impact, and your impact on the world. This is likely why there's a rising desire for operators to work for organizations that 'have more meaning' or a 'sense of purpose' to do good in the world. This article is a starting point that investigates business growth at the expense of user value, while also sharing investments you can make immediately to put change into practice.